When people tell me to "picture this," I can't. I have aphantasia, a condition where one cannot voluntarily generate mental images. While you might close your eyes and conjure up a sunset or a loved one's face, my mind's eye sees only darkness.

I'm not alone. Research suggests that approximately 2-4% of the population have some level of aphantasia; many will go a lifetime without realizing their experience differs from others. The condition was first documented by Francis Galton in 1880 and rediscovered/named in 2015 by Adam Zeman et al. Aphantasia is a fascinating variation in human cognitive experience and may gesture toward the future success of multimodal AI technology.

Like me, the co-founder of Pixar, Ed Catmull, discovered late in life that he had aphantasia, and talked publicly about the curious relationship of visualization and creativity. I was delighted, when I first arrived at University of Utah as Dean of Humanities in 2022, to learn that he was an alumnus. I was looking forward to a general awareness of the condition on campus.

The explosion of research in the last few years reveals something remarkable about how our brains process information. According to Zeman (2021), "Visualization is 'vision in reverse': The brain begins with a decision or instruction—'imagine a tulip'—and uses its stored knowledge of appearances to drive activity within the visual system." For those of us with aphantasia, this reverse process doesn't activate the visual systems the same way. Yet around 60% of people with aphantasia – including myself – report visual dreams, suggesting that the neural pathways for visual imagery remain intact. What's affected is our voluntary control over these pathways.

Recent research has revealed further complexity in this condition. Takahashi et al (2024), examining nearly 2,900 individuals, found that aphantasia isn't simply a matter of having or not having mental imagery. Some individuals experienced a complete absence of all sensory imagery, while others might have varying degrees of difficulty across different sensory modalities. Some might struggle only with visual imagery while maintaining vivid auditory or tactile imagination.

What people should understand about those of us with aphantasia is that our alternative problem-solving strategies can be superior to visualization-based approaches, particularly our ways of processing information through relationships, facts, and logical frameworks rather than visual imagery. Many of us have been highly successful in creative and leadership roles despite “lacking” what most consider a fundamental cognitive ability.

Recognizing aphantasia can offer profound insight into cognitive diversity: two people can be equally capable while having radically different inner experiences and mental processes. Imagine thinking about diversity in terms of invisible processes. Imagine how much richer AI output can be with multimodal capacity.

For me, the challenge of having aphantasia is in navigating a world built on the assumption that everyone can "envision" things equally well. When a friend says, "Can you picture how this outfit will look?" or an art gallery owner asks me "imagine how these three pieces will hang near each other," I'm reminded of this invisible difference. People assume a universal level of visual thinking and mental modeling.

As an academic leader, I’m particularly interested in the new studies about how aphantasia affects academic and professional performance. Eker, Özer & Gençel (2024) found that aphantasic students achieve higher undergraduate grades than their non-aphantasic peers. Aphantasic individuals develop alternative learning strategies that sometimes improve rather than inhibit learning. They also found that people with aphantasia tend to be more "professionally oriented" in their learning style, perhaps drawing on habits of using analytical and systematic approaches to processing the world.

This finding aligns with my own experience. Because I never thought my brain processed the world differently than anyone else, I assumed everyone was interpreting information as I was. I built robust systems of verbal memory and logical reasoning, analyzing through patterns, relationships, and concrete details. I read lots of poetry, which I heard as sounds and saw in shapes. I didn’t see daffodils. I assumed that Wordsworth’s "mind's eye" was a metaphor – I never thought that some people actually had a mind's eye.

The distinction between voluntary and involuntary imagery is crucial for understanding how aphantasia affects daily life. When friends ask, say, what country I’d like to visit again, they may not know they’re requesting voluntary visualization, the way most people imagine themselves in this city or that country. But people with aphantasia, Blomkvist (2023) notes, engage multiple cognitive systems: "You must be awake and attentive, you require your command of language to decode the instruction, you need your memory to retrieve knowledge, you need to use your executive function to orchestrate the whole process."

Takahashi et al report that two thirds of individuals with aphantasia studied had difficulties with autobiographical memory, such as remembering places they've been. When asked to describe the layout of their own homes, persons with aphantasia may rely on "spatial knowledge" rather than visual imagery. We might not be able to "picture" a location we've visited, but we can often accurately describe features drawing on a database of facts rather than a mental photograph.

And indeed I tend work from abstract knowledge rather than visual previews. I have watched while traveling companions without aphantasia are more at ease in new airports or train stations than I am – they have a mental map of how airports work and glide through them easily. I have a cognitive map based on logic which works just as well but takes more thinking work and mental bandwidth. In new cities or going to a new place in my own city, I pay close attention to verbal directions and focus on logical relationships between landmarks rather than visual memories of them.

It's all good – better, now that I know what my brain is doing! But I also see how the digital world – where everything is virtual -- has amplified these challenges for those of us with aphantasia. A helpful store clerk who might have physically shown me to an item is replaced by an app that expects me to know how and where to click on something.

It is wonderful to live in a world that now celebrates neurodiversity and cognitive difference, that recognizes the rich diversity of human thought and experience. Those of us who think in words, sounds, relationships, concepts, and patterns aren't failing to visualize – we're simply processing, recalling, and navigating the world differently

Now that we have a name for the lack of visual imagery, I think about challenges I’ve had in the past and how certain technologies – like GPS in every car – have transformed my life for the better in the present.

But still, I encounter people who see hesitancy in easy visualization as a lack of intelligence. This becomes apparent in the corporate realm, which often sees itself in org charts and workflows. People steeped in org charts don’t tend to understand why I ask the questions I do.

My own way of succeeding in a complex organization (which is what higher ed is these days) depends on relationships rather than boxes and flow charts. I am known for being particularly present and communicative, attentive to relationships between people and information. Interpersonal trust matters more than anything else to me in navigating complex networks and hierarchies. Trust operates like a cognitive shortcut.

Recent philosophical analysis of aphantasia looks at the underlying cognitive mechanisms. Lorenzatti (2023) evaluates four competing hypotheses about aphantasia and concludes that aphantasics are not merely failing to access or describe mental imagery that exists, but rather lack visual imagery entirely while developing distinct cognitive pathways. This analysis helps explain why aphantasic leaders' success isn't just about compensation or adaptation, but rather reflects fundamentally different ways of processing organizational information.

The philosophical framework provided by Lorenzatti suggests that when organizations assume visual thinking is universal, they may be overlooking diverse cognitive approaches that could enhance collective decision-making. Rather than focusing on helping aphantasic leaders overcome a perceived deficit, organizations might benefit from understanding and leveraging their natural tendencies toward systematic analysis, relationship-based understanding, and logical frameworks. This perspective suggests that cognitive diversity in leadership teams - including both visual and non-visual thinkers – could strengthen an organization's ability to navigate complex changes and challenges. Imagine bringing a multimodal AI to the table.

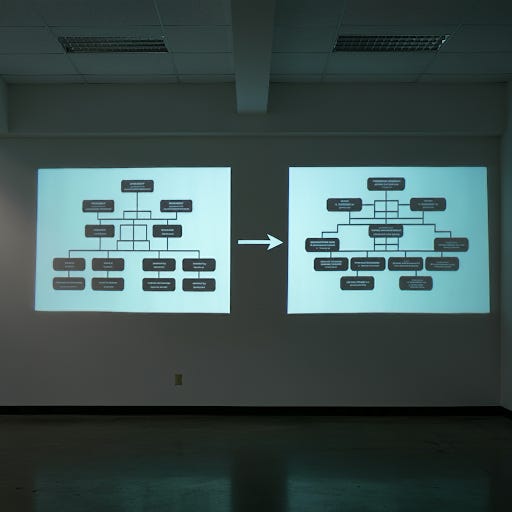

Say there is a corporate reorganization underway. There are slides showing current organizational charts transitioning into new ones, with the assumption that one can "picture how these teams will work together" or "envision the future state." For me, sitting in a meeting about a reorganization is complicated.

The standard approach to organizational change relies heavily on visual thinking and mental modeling. Presenters show "before and after" slides, with the expectation that everyone can hold both states in their mind while mentally animating the transition between them. They ask people to "visualize" how workflows will change, "picture" new reporting relationships, and "imagine" future scenarios. For someone with aphantasia, this is impossible.

Consider the typical elements of a reorganization presentation:

"Here's where we are now" (diagram on the left)

"Here's where we're going" (diagram on the right)

"Can everyone see how this will flow?"

"Imagine your team in the new structure"

"Visualize how information will move in this new model"

As a leader with aphantasia, such a presentation creates a double cognitive load. Not only must I attempt to process actual organizational changes, but I need to translate the visually oriented presentation into non-visual understanding. For me, it is imagining the ‘who’ who will be doing new tasks and their relationships with others.

That is, I cannot simply "envision how the team will operate in the new structure" or "picture this person in a new role," I need to ground change in logic – why is the change needed, how will the new process meet the need, how people will report to different people, and how outcomes will be measured. I can’t tell you the challenges I’ve faced endeavoring to translate visual information about an organizational change into logic when the logic isn’t readily apparent. There are people for whom asking questions seems obstructionist rather than simply an alternative way of processing.

(I will write soon about how AI may deliver a mortal blow to consultant-led reorganizations internationally.)

The challenge of reorganization highlights a broader truth about aphantasia in professional settings: it's not just about being unable to picture things; it's about navigating a world that assumes visual thinking is universal. As organizations become more aware of cognitive diversity, they might begin to recognize that effective change management needs to accommodate different ways of processing and understanding organizational transformation.

The real work of change happens through relationships, logic, and systematic understanding – areas where aphantasic leaders, as well as multimodal AI, can excel. As we build more cognitively inclusive workplaces, we're not just making space for different ways of thinking – we're unleashing the full potential of human and AI innovation.

The corporate world's reliance on visual thinking is particularly interesting in light of Blomkvist's research showing that aphantasia is best understood as a condition affecting the "episodic system" – how we process and recall experiences. When presenting organizational changes, we're not just asking people to visualize boxes on a chart; we're asking them to imagine future scenarios and recall past experiences in a specific way. But those of us with aphantasia store things differently and recall things differently. Aphantasic individuals can successfully perform complex tasks by drawing on what participants described as "knowledge," "memory," and "subvisual models."

In short, those of us with aphantasia aren't failing to visualize – we're pioneering alternative ways of understanding and leading change. In a world of increasing complexity, perhaps this diversity of cognitive approaches isn't just something to accommodate – it's something to celebrate

Notes:

Blomkvist, A. (2023). Aphantasia: In search of a theory. Mind & Language, 38(3), 866-888.

Eker, Ö., Özer, B., & Gençel, N. (2024). Effect of aphantasia on academic achievement and learning styles in higher education. International Journal on Studies in Education, 6(4), 644-657.

Keogh, R., Pearson, J., & Zeman, A. (2021). Aphantasia: The science of visual imagery extremes. In J.J.S. Barton & A. Leff (Eds.), Handbook of Clinical Neurology: Neurology of Vision and Visual Disorders (Vol. 178, pp. 277-296).

Lorenzatti, J. J. (2023). Aphantasia: a philosophical approach. Philosophical Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2023.2253854

Takahashi, J., Saito, G., Omura, K., Yasunaga, D., Sugimura, S., Sakamoto, S., Horikawa, T., & Gyoba, J. (2023). Diversity of aphantasia revealed by multiple assessments of the capability for multi-sensory imagery.

Zeman, A., Dewar, M., & Della Sala, S. (2015). Lives without imagery–Congenital aphantasia. Cortex, 73, 378-380.

Zeman, A. (2021). Blind mind's eye. American Scientist, 109, 110-117.

I suspect aphantasia is more widespread than we realize, at least that is what I gather anecdotally. The difficulty with autobiographical memory is especially sad for me. Unlike what you describe about spatial awareness, though, I find that mine is quite strong. I've also noticed a weird thing my brain does that I wonder if others with aphantasia experience. I listen to a lot of podcasts and audiobooks while walking my dog in my neighborhood. When I reflect on stuff I've listened to afterwards, I immediately recall exactly where I was walking or standing when I heard this or that bit of information. There is always a spatial/locational element to my recall. Is this something others have experienced? I am looking forward to this condition being further studied and elucidated.

- Could you describe how you may generate the reorganisation presentation, just as an example of how you think in terms of "relationships, logical patterns, systematic thinking"? Do non-aphantasia people share this sort of thinking (but maybe in a weaker form)?

- Could you elaborate on what you mean when you said "Trust is the cognitive shortcut" - did you mean that if two people trust each other, it's easier for you to infer their shared knowledge?

- I'd like to experiment with myself, as in trying to tune out my ability to visualise and think like a person with aphantasia. Would you have any idea on how that could be done?

Thank you!!