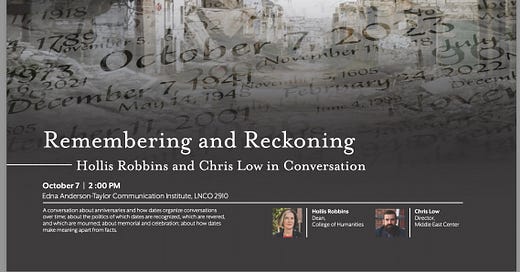

As some of you know who follow me on other social media, I participated in a conversation with our university’s Middle East Studies director, Chris Low, to mark the one year anniversary of the attacks of October 7 that have, as headlines proclaim, changed higher ed.

This is not a post about the ongoing violence, destruction, displacement, carnage, and the breaking of international laws. This is about how I think universities should be engaging with it all.

As Dean of Humanities, I oversee seven departments and eight centers and programs, including the International Studies Program, the Center for Latin American Studies, the Asia Center, and the Middle East Center. I took the position in part because of the international breadth of the college, beyond the traditional humanities disciplines of English, history, and philosophy.

In the best of worlds, expert faculty would be prepared to talk knowledgably about current events, issues in the news, decisions being made around the globe of interest to staff, students, and faculty, as well as to the community outside the campus gates. The availability of expert faculty to talk about issues in the news is one of the key values a university brings to its community. As I wrote in my last post, last month I attended a convening at Stanford on the “academic social contract” between universities and the state, the agreement of universities to provide research, professional training, education, and culture to citizens and members of the community broadly in exchange for public support in the form of special charters, tax exemptions, and subsidies. To put it in neoliberal terms, universities cultivate human capital and return it to the public.

I am lucky to have in the College a brilliant and energetic scholar in Chris, who as Director of Middle East Studies, shares the view that faculty should seek to educate, not agitate. He had only been Director for four months on October 7, 2023.

That morning I texted him – text is my preferred communication method with chairs and directors, as it presumes an ongoing relationship, without hello and goodbye – offering him my support, wondering, as we were just beginning to rebuild our Middle East Center after many years of dormancy, whether he would be called on to talk about the attack, the history and tensions that led to this attack, and what would follow. By 5:00 that evening he had received his first media inquiry, which he declined, and we texted nonstop as we each watched on TV and Twitter, in a kind of horror on top of horror, how polarized the response was, particularly on campuses, where there was either cheering for Hamas or calling on Netanyahu for immediate, bloody revenge.

Let me pause here to say that Chris, who got his PhD from Columbia in 2015 and knows all the key figures in Middle East scholarship, has the academic training to speak fluently about current events. He has done language training, archival work, and/or traveled in Egypt, Israel/Palestine, Kuwait, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. He knows Palestinian history and perspectives. He makes clear that that dispassionate analysis and criticism of Israel is a normal function of Middle East Studies scholarship, and that this criticism is not antisemitism.

It was clear within 24 hours that as a dean with both Middle East Studies and Jewish Studies in my College I had to make an intentional choice to focus on education rather than platforming sides and that if I did not make an intentional choice, it would be made for me. We had multiple constituencies – students, faculty, staff, the legislature, the community. If such a thing as an academic social contract exists, the goal of a university should not be institutional neutrality but rather education.

By October 9, given the immediate polarization, my team was in conversation with Student Affairs, the President’s office, and faculty with Middle East specialties across the university about how to talk about what had happened, what was about to happen, both in the region, as a matter of the initial attack, the anticipated reaction, the carnage, and what was probably going to happen on university campuses.

What we did was organize an educational panel, which we held on October 19 for Student Affairs staff and leaders. The panel included the Director of the Middle East Center (Chris), the head of Jewish Studies, a professor of political science widely published on secularism and Muslim democracies, and a post-doc scholar who studies Ottoman Iraq.

The goal was civil and educational dialogue, of heightened importance given the violence and pain. University leaders are expected to have some understanding of world events, especially those that have caused so much hurt and pain locally and around the world. On a subject like the recent violence in Israel/Gaza, there is a wide range of understanding. I noted that we had assembled on the panel about 100 years of focused study. Each spoke from their discipline about what was unfolding and what questions were being raised.

I spoke solely from my expertise in the history of academic freedom and free speech on college campuses. I noted that the AAUP — American Association of University Professors — definition of academic freedom is "the freedom of a teacher or researcher in higher education to investigate and discuss the issues in his or her academic field, and to teach or publish findings without interference from political figures, boards of trustees, donors, or other entities. Academic freedom also protects the right of a faculty member to speak freely when participating in institutional governance, as well as to speak freely as a citizen.” The AAUP also cautions: "faculty members [should] be free from institutional censorship or discipline when they speak or write as citizens, but they also [have] special obligations. When speaking on public matters, faculty should strive to be accurate, should exercise appropriate restraint, should show appropriate respect for the opinions of others, and should make every effort to indicate that they are not speaking for the institution.”

What is said on the quad or lawn with signs is a matter of free speech. And to return to the idea of an academic social contract, the responsibility of a university is to create experts, to fund research, to platform speech that emerges from expertise. Platforming protest is not part of the academic social contract.

This past year was not my first time working with faculty as violent events were unfolding. In April 2015 I was Director of the Center for Africana Studies at Johns Hopkins University during the murder of Freddie Gray and in the midst of the Baltimore uprising that followed. Every local and national print and broadcast news media was on the phone and for about two weeks the task was to platform faculty who would speak to the research the Center had been working on for years about the Baltimore police, about the lack of oversight of the brutal methods being used, about the lead paint Freddie Gray had been exposed to more most of his childhood, and the role of the University in serving as a site of conversation about the murder and investing in solutions.

I expected that the past year would involve ongoing intense conversation about events in the Middle East, and it has. What have we done differently from other campuses? We have built capacity and expertise in Middle East scholarship: three tenure-track hires, one post-doc, a new series out of University of Utah press, op-eds, local TV and radio appearances, new donor and community engagement, and a new course on the history of Israel and Palestine. Chris brought in distinguished Jewish scholars who integrate Israeli and Jewish history with Palestine, Lebanon, and Iran rather than framing the conversation as oppositional camps. We’ve started a Middle East reading group that includes Muslim, Druze, Christian, secular, and Jewish faculty, together.

We had perhaps two reasons to mark the anniversary. The first is that the attack on the morning of October 7 offered the opportunity to work together and to teach, in fulfillment of the academic social contract. That work has been productive and real.

The second is to mourn, because no matter what community each of us is from, it has been a horrific year. So we sat together and remembered. One faculty member noted that we don’t always have a place to remember in a personal way, as teachers and leaders. We don’t get to say what punches us in the gut. This is not a sides issue. There has been enough gut punching to go around. And we’ve worked to make a safe and sane space as a community of scholars and a community to be able to simply remember.

We decided to have a conversation because amidst the carnage that is still going on the College is a place for discussion, frank assessment, and learning. Chris exemplifies the role of a Center Director in a time of global crisis, addressing events head on, advocating for new faculty, supporting our new Diplomacy program, as we think about training students for careers in negotiating conflicts.

I am in a funny position as a Jew from a family who is not oriented toward Israel. My grandfather, from Lithuania, was a postman and staunch American. My grandmother, whose family in Latvia were almost entirely wiped out in 1941, was a committed American. Neither one set foot in Israel. For many years I was married to a man whose family was deeply invested in Israel. It was new to me. We went to Israel on our honeymoon. It is an important place to me even while it is not my country. This is a nuance that escapes a lot of good people on campuses and a lot of not-so-good people. I am a dean who is Jewish, not a Jewish dean. I support all our students, staff, and faculty, wherever they’re from, whether they are Zionist or anti-Zionist. And I will continue to do so.

The advice I would have given to every university president last year (if asked) is: make allies of your Middle East faculty. Meet with them regularly. It’s good advice still today.

-