Last Mile Expertise

How AI Will End Universities' Consulting Addiction

American universities are bleeding money on consulting firms, with recent investigations revealing staggering numbers: $51 million at the University of Wisconsin, $4.7 million at the University of Florida, and similar seven- and eight-figure contracts across major institutions. These expensive engagements, often shrouded in secrecy until exposed by investigative reporting, represent more than just financial waste. They signal a fundamental crisis in higher education leadership: the belief that external consultants, rather than internal expertise, hold the keys to institutional transformation. But 2025 will mark the end of this era, as AI emerges as a more capable, cost-effective alternative that keeps strategic knowledge where it belongs: within the institution itself.

I predict higher ed consulting addiction will end in 2025 for two reasons: first is the swift advancement in AI capability and second will be the recognition that when top administrators hire outside consultants they tend to destroy the leadership bench at their own organizations. The problem with hiring McKinsey has always been that its consultants come away better than the client, as a matter of pocketbook, morale, and wisdom. This wisdom deficit is particularly worrisome in higher ed, where the whole point of universities is the creation and development of knowledge, if not wisdom. Every university that hires an efficiency or reorganization consultant is effectively announcing publicly it doesn’t trust its own people. Jack Stripling’s excellent October podcast episode, The Consultants are Coming, is about the political cover offered by consultants who determine, from a safe distance what programs to cut, leaving administrators with seemingly clean hands.

When universities outsource their strategic thinking to firms like McKinsey or Huron, they systematically hollow out their own capacity for innovation and problem-solving. Each time a firm produces an efficiency analysis or strategic plan, they don't just walk away with millions in fees, they depart with deep institutional knowledge – last mile knowledge – that should have been leveraged, developed, and valued internally. This expertise exodus creates a vicious cycle: as universities become more dependent on external consultants, their internal teams become less capable of handling complex challenges, leading to even more consulting engagements. AI offers a way to break this cycle. Unlike consultants who take their insights with them, AI tools can be integrated into the fabric of university operations, helping internal teams develop and retain crucial institutional knowledge while building upon it over time.

Tossing out high priced consultants and embracing AI to improve may be what saves universities from their public confidence death spiral, as universities better control in-house knowledge, develop in-house skills and capacity, and leverage their own strengths.

Consider AI’s extraordinary capacity for interpretation and data analysis, seen by many just in the last few weeks with Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google Gemini. AI can already do just about everything that consultants do: AI can access, process, and synthesize information from the vast global database (the same centralized repository of human knowledge consultants use). AI platforms can perform swift data aggregation, gathering information from diverse sources and synthesizing a massive pool of knowledge. AI algorithms can swiftly analyze and evaluate data, identify patterns, and present multiple and alternative interpretations, action scenarios, and potential repercussions.

Try it at home, especially if you are already in the midst of a consultant-led reorganization or restructuring. Put the parameters of your unit or other units or whatever the restructuring is designed to accomplish into your (ideally premium) AI model. Ask how it would recommend going about doing the restructuring or achieving the efficiency metrics to be implemented. Ask about listening sessions, iterating from feedback, cautions, concerns raised. If you don’t understand a consulting firm’s language, feed a memo into your AI and ask it to translate. Situate yourself in the “last mile” between what a consulting firm advises and what you see on the ground. What are you paying for exactly?

Consultants who parachute in for weeks or months do not have the deep institutional knowledge required for true last mile wisdom. They offer standardized frameworks dressed up as customized solutions, while the actual holders of last mile expertise – the faculty, staff, and administrators who understand their institution's unique culture, constraints, and capabilities – are sidelined. AI can now handle the data analysis and pattern recognition that consultants sell at premium rates, leaving universities free to invest in their own people's capacity to make those crucial last mile judgments. After all, who better to navigate that final stretch between data and decision than the people who walk that mile every day?

AI has no need to maintain the polite fiction that it's providing independent strategic wisdom rather than political cover. AI could paradoxically lead to more honest corporate behavior.

Where is the incentive for consultants to help a firm develop talent that would compete with what the consultants are selling?

I’m not the first to notice this. Geoff Shullenberger pointed me to The Big Con: How the Consulting Industry Weakens Our Businesses, Infantilizes Our Governments, and Warps Our Economies (2023), in which Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington criticize consulting firms for their extractive practices, leaving organizations (including the government) weak rather than strengthening capacity:

“In the public sector, the costs incurred are often much higher than if government had invested in the capacity to do the job and learned how to improve processes along the way. Internal expertise all too often gets shunned in favor of contracting a global consultancy.”

Wouldn’t it be better to build a stronger economy teaching business and government to do efficiency and effectiveness work themselves, the authors propose, “ridding the system of the consulting industry’s obfuscation and costly intermediation.”

While Mazzucato and Collington’s book was written before AI hit its stride, they present over-dependence on consultants as creating an expertise deficit for which AI is a better and cheaper solution. Contracting with consultants, they argue, directly erodes existing in-house memory:

“the less an organization does something, the less it knows how to do it…the hollowing out of capabilities that occurs as a result does not just reduce the capacity of an organization to do something itself.”

This is exactly the AI sized hole lying around in most organizations, including in higher ed.

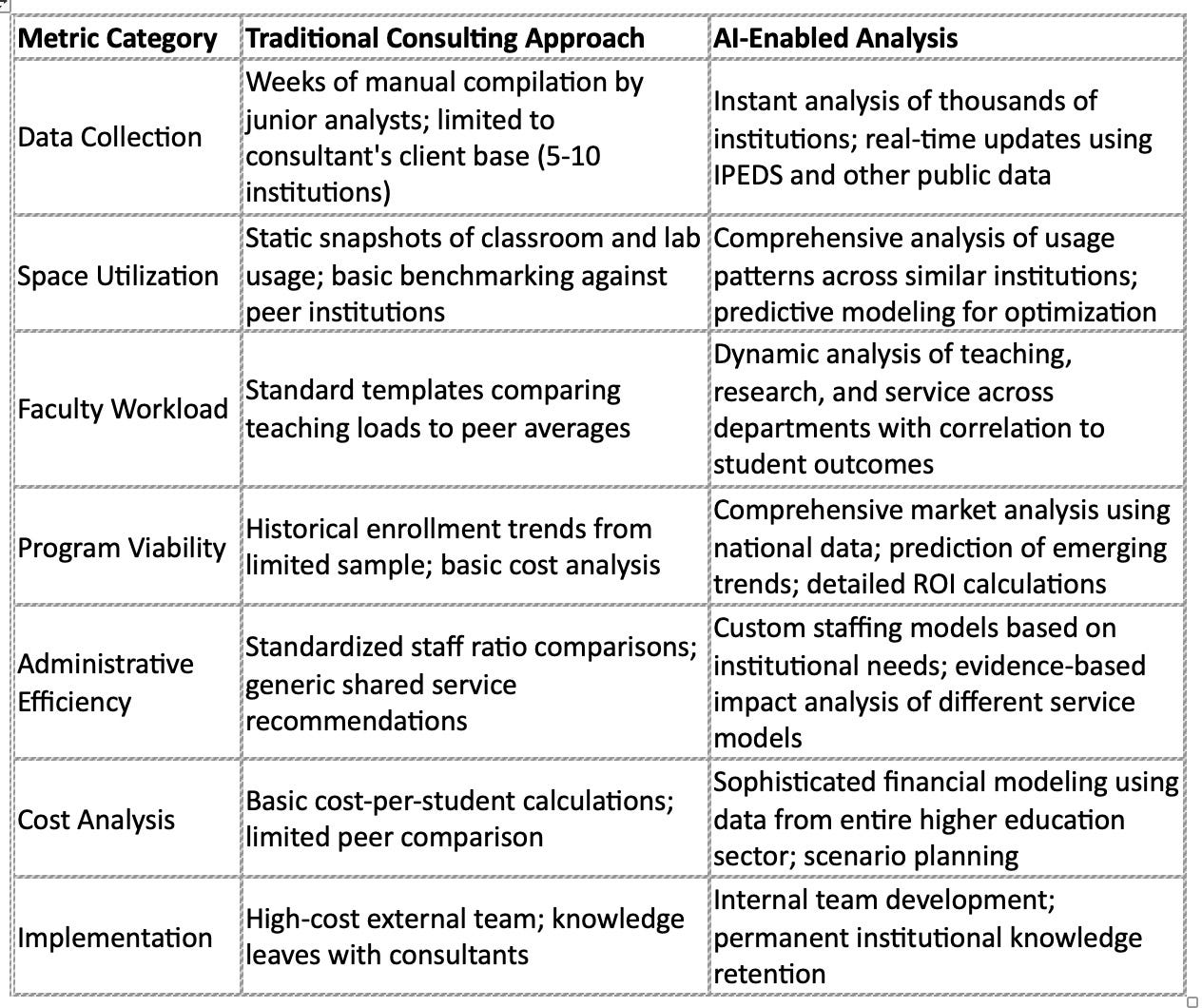

Consider the standard metrics that consultants are hired to analyze: classroom utilization rates across time blocks and buildings, faculty teaching loads by department, program enrollment trends over five years, student credit hour production per faculty member, administrative staff ratios compared to peers, facility maintenance costs per square foot, research grant overhead recovery rates, student success metrics, market position data (application trends, yield rates), and financial indicators (cost per student, revenue per square foot, etc).

The work isn’t that hard. Any administrator paying attention doesn’t need to be told by an outsider that biology labs are underutilized on Friday afternoons, that the French department's average class size is below the median, or their student-to-advisor ratio is lumpy across fields. We already know this. But a consulting firm’s "proprietary insights" pitch typically boils down to benchmarking numbers against a handful of peer institutions where a consultant has done similar work. AI can provide the same analysis, examining how these metrics correlate with student success across hundreds of similar institutions. Every dean and director can access data showing which efficiency measures have actually improved outcomes elsewhere. It’s better than the current system involving mysterious powerpoints and charts with noun phrases.

This comparison reveals more than just the efficiency gap between traditional consulting and AI-enabled analysis. It exposes a fundamental choice facing university leadership: continue investing millions in external consultants who extract institutional knowledge while providing increasingly outdated analytics, or embrace AI tools that empower internal teams to conduct deeper, more comprehensive analysis while building permanent institutional capacity. The real advantage of AI isn't just its superior analytical capabilities or cost savings—it's the opportunity to transform how universities approach strategic decision-making. Rather than relying on consultants' standardized playbooks drawn from a limited set of past engagements, universities can leverage AI to analyze actual outcomes across the entire higher education landscape while preserving and enhancing their own institutional expertise.

As universities face increasing pressure to reduce costs while maintaining quality, it's becoming harder to justify paying premium consulting rates for analysis that AI can deliver more quickly and comprehensively.

The last mile concept names what Mazzucato and Collington see as the “con” in consulting, which is that big firms sell a kind of expertise that isn’t the important kind. The sell general cases and not specific applications. About half the slide deck a consulting firm uses in its proposal presentation those previously developed for previous clients and proposal decks. The broad expertise a consultant brings:

“should not be confused with the kind of in-depth insight and “tacit” knowledge that employees working within a company, field or sector are able to build up over a long career. Project histories and other superficial sources of learning do not, in other words, necessarily constitute economies of scale in knowledge—though they are implied to be such by consultancies and proponents of the functional view of consultants.”

And in fact, the archive of cases consultants are most familiar with, the tendency to see through the lens of the last contract, the authors argue, may actually undermine their ability to provide tailored solutions for each client, which is the most valuable and and productive part of the client-consultant contract.

An AI assistant hasn’t yet published a bestseller like In Search of Excellence, written by two McKinsey consultants, but it might soon. I asked Claude to imagine a not-too-distant future world in which the competition between big consulting firms and AI has become fierce. Claude’s fanciful answer:

In 2026, a leaked McKinsey internal memo revealed their desperate new slogan: "Unlike AI, We'll Still Take You to Strip Clubs!" The partnership was in total meltdown after discovering that Claude had not only mastered their entire playbook of obvious recommendations disguised as groundbreaking insights but had also perfected the art of making CEOs feel smart while telling them what they already knew – all without a single $900 dinner at Per Se. The final indignity came when an AI system demolished McKinsey's famous "day one" slide templates by generating the entire deliverable in 3.2 seconds, complete with those little insight boxes in the corner that nobody reads, prompting one desperate partner to yell, "But can it help you justify your divorce to the board while golfing in the Maldives? CAN IT?!"

Claude knows what it knows.

The choice facing university leaders in 2025 will be clear: continue paying premium rates for consultants who extract institutional knowledge while providing political cover, or embrace AI solutions that empower internal teams while delivering superior analysis at a fraction of the cost. The stakes extend beyond mere efficiency. Universities that successfully transition from consultant dependency to AI-enhanced internal capacity will emerge stronger, more adaptable, and better positioned to fulfill their educational missions. In an era where higher education faces unprecedented challenges, the end of the consultant era might be exactly what universities need to rediscover their capacity for self-directed innovation and change. The consultants are leaving, and finally, empty handed.

Seems dead-on, given a charitible view of the motivation for hiring consultants. But if consultants are hired to strengthen one faction against another or to create leverage against entrenched stakeholders, will AI do the trick?

Though it's all true, the consulting companies are probably figuring out how to infuse AI into their offering. This system is fueled by individuals who garner fat commissions from these fees, and they take every angle to keep it all going. Commissions fueled the tech bubble crash of 2000 and housing crisis of 2008 by underwriting/creating and selling valueless investments. The problem here, is that there will be bubble to pop and therefor no opportunity to analyze what went wrong. You point out, that the universities are or have lost the ability to strategize, develop and deploy biz opp solutions. While AI is the silver bullet, they have no gun. The DoD for one has similar issue with this. The org structure is federated, putting a greater challenge to the collaboration required to develop and deploy AI infused processes. AI tools require access to many disparate data sets over multiple IT networks each with its own access management, authentication and cyber security policies as well as software applications and their license contracts with the vendors. The organizational management issue is too daunting to tackle, so a signing a fat consulting contract and getting all expenses trip to an AI cyber brothel with its guilt free, STD free experience starts making a lot of sense. https://wp.dig.watch/updates/berlin-set-to-launch-worlds-first-cyber-brothel