I come to praise Sisyphus, not to bury him, because he is already buried, as legend has it, condemned by the gods to roll a rock up a hill forever.

– The Odyssey Book 11 (Fagles translation)

Who does not sometimes feel like Sisyphus? So tragic and yet so funny! So relatable, as the kids say.

But what if we have been reading him wrong? What if Sisyphus’s burden was never truly a burden at all, but simply the codification of something he would have done anyway? What if the gods, rather than condemning him, were simply defining him?

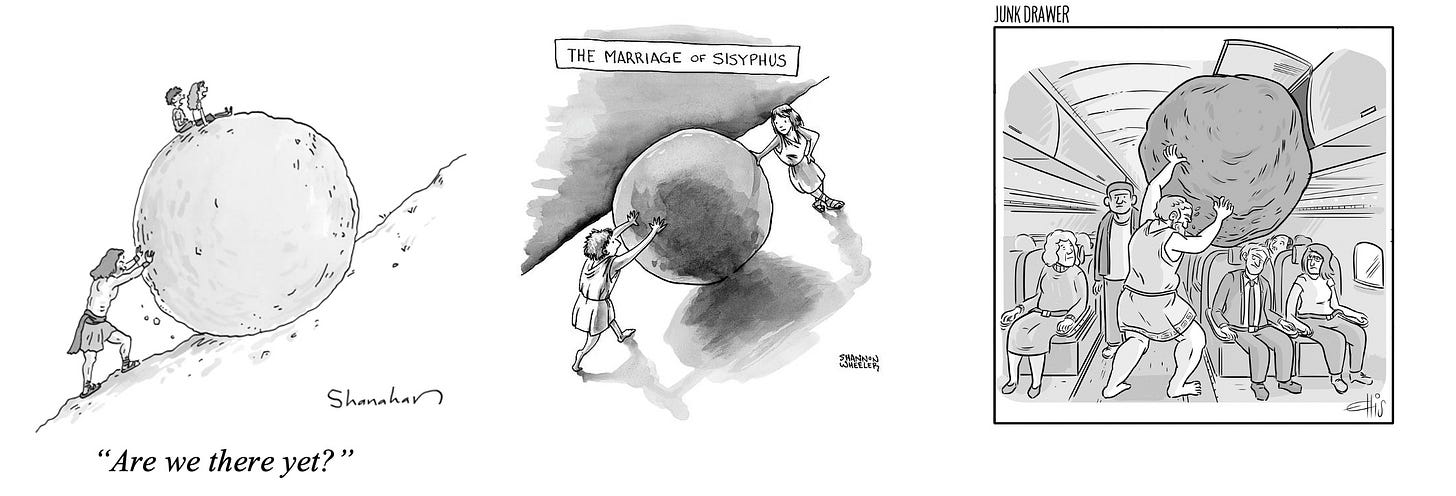

I spent the morning laughing at Sisyphus cartoons from The New Yorker. The genius of Sisyphus as a comic figure is the elegant simplicity of his predicament. Cartoonists, take it away:

We have Albert Camus and existentialism to thank for reviving Sisyphus from Homer’s tragic view and giving him a comic afterlife. In “The Myth of Sisyphus” (1942) Camus asks us to imagine what Sisyphus is thinking. Or more formally, in the context of so much absurd global upheaval and bloodshed, Camus wonders what Sisyphus, “proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious,” is thinking as he walks down the hill after every failure. Is he angry? Sorrowful?

If this myth is tragic, that is because its hero is conscious. Where would his torture be, indeed, if at every step the hope of succeeding upheld him? The workman of today works everyday in his life at the same tasks, and his fate is no less absurd. But it is tragic only at the rare moments when it becomes conscious.

Sisyphus is the absurd hero. Or it may be that life is absurd. And as it was for Oedipus, Camus argues, the tragedy begins with knowing.

It is shocking to me that Freud never wrote about Sisyphus, as he did about Narcissus. Freud might have said some very smart things about work without end. So might have Nietzsche, though his “eternal return” is very close.

Camus carries the whole burden of recognizing and elevating the simplicity of Sisyphus’s story to the top of our consciousness, where it hasn’t rolled back down. I don’t have access to the complete New Yorker cartoon archive but I didn’t find any Sisyphus cartoons in the magazine prior to 1942.

Reframing Sisyphus’s plight as a metaphor for modern, mechanized existence opened the possibility of transforming frustration with factory work, corporate bureaucracy, new technology, fitness goals, inbox management, into humor.

Was the myth of Sisyphus always funny and nobody noticed until Camus?1 Do the gods get credit for the humor? Probably not. The vast pantheon of Greek mythology is not about funny characters. (The Romans were funny. We can argue.)2

Sisyphus’s plight can be grasped immediately: he pushes a boulder up a hill, it rolls down, and he begins again. With this clean setup, modern parallels can land instantly.

The story is the punishment, not what Sisyphus did to earn it. The backstory is diffuse and various. Basically, he angered the gods. Here’s a synopsis:

Sisyphus was king or founder of Corinth. One day he saw Zeus carrying off the river-god Asopus’s daughter, Aegina, to ravish her. Sisyphus told Asopus he would trade information for a spring of fresh water. Zeus punished Sisyphus by sending Thanatos to take him to Hades. Sisyphus tricked Thanatos by binding him in chains (this part is funny) so there was no more death for a while. The gods, finding war no fun without death, sent Ares to release Thanatos. Sisyphus was on the run again. But he planned ahead by asking his wife, Merope, when he was near death, to throw his body unburied in the town square, without the usual burial rituals. Hades was so appalled at such a disloyal wife he let Sisyphus return to the upper world to punish Merope. Once up top, Sisyphus said why would I go back? So he stayed in Corinth and lived a long life, near his spring.

You could figure out a way to say the punishment fits the crime but that makes the boulder-pushing less interesting

The gods’ choice of punishment is exquisite because of its transferability to everyday life, which can be absurd, repetitive, futile, and hilarious. AI should grasp it and riff on it. And it does! Here is DeepSeek, when asked for some jokes:

Sisyphus walks into a gym.

Trainer: “What’s your fitness goal?”

Sisyphus: [sighs] ”Maintenance.”Why did Sisyphus start a podcast?

He wanted to turn his eternal struggle into an infinite content loop.Sisyphus’s coworkers asked how he stays motivated.

He said, “I just focus on rolling with the punches. Literally.”

They aren’t bad. I asked Claude 3.5:

Q: What did Sisyphus say when asked about his workout routine? A: It’s an uphill battle, but I’m really pushing myself.’

Q: Why did Sisyphus make a terrible project manager? A: He kept rolling out the same deliverable over and over.

Q: What’s Sisyphus’s favorite Beatles song? A: ‘The Long and Winding Road’ – though he never makes it to the end.

Also not bad. There’s something profound here, at the intersection of comedy, existentialism, and algorithm. The best jokes are surprisingly obvious. They are recognizable. Predictable and surprising at the same time. They are a template.

I’m reminded of this observation by Pierre Bourdieu in Outline of a Theory of Practice (1972):

If witticisms surprise their author no less than their audience, and impress as much by their retrospective necessity as by their novelty, the reason is that the trouvaille appears as the simple unearthing, at once accidental and irresistible, of a buried possibility. It is because subjects do not, strictly speaking, know what they are doing that what they do has more meaning than they know.

You can say Camus bringing Sisyphus into the modern world was just the simple unearthing of a buried possibility that had been there all along. The best jokes operate on raw pattern recognition and quick associations, shortcutting wisdom to a deeper logic. Puns work this way – how odd that one word means this and that and how polite company pretends it doesn’t! (I’m thinking of Shakespeare and Donne on country pleasures.)

I tested this hypothesis and asked the expensive ChatGPT Pro to give me some Sisyphus jokes and they were terrible. Terrible!

Q: Why did Sisyphus refuse to join the band?

A: Because he was already stuck with “rock and roll.”Sisyphus once tried to find a job with better work-life balance. He quit on the first day—something about the new gig still being an uphill battle.

Sisyphus tried booking a relaxing getaway. He got as far as packing his bags, but by the time he turned around, his vacation rolled right back down the hill.

Really? The badness! I said try again.

Sisyphus and his boulder walk into a bar. The bartender shouts, “Hey, we don’t serve rolling stones in here!”

Sisyphus just shrugs: “No worries. We never gather any moss anyway.”Rumor has it Sisyphus tried opening a fancy espresso bar at the top of the hill. By the time the espresso machine arrived, it rolled right back down.

He decided to rename the place Déjà Brew—because every cup felt like starting from scratch.3

Oy!

When the most sophisticated LLM, trained to reason, analyze, and carefully consider implications, fails at Sisyphus jokes, there is something crucial about intelligence to be learned. The best AIs have been trained to reason, to see homophones (for example) as a problem to be worked around for output precision. But thoughtfulness is death to comedy. The simpler AI sees ‘Sisyphus’ and ‘rock’ and just riffs. Pro is busy contemplating the philosophical implications of eternal recurrence. Is it — are we —like Sisyphus, constantly rolling the boulder of meaning up a hill?

The ability to be funny is not an advanced cognitive function that sits on top of the capacity for logic and reason. Humor is more primitive, more fundamental. It is accidental unearthing of buried possibility. If cheaper AIs can crack better jokes than the expensive ones, that suggests that humor is more of an instinct than an intellectual achievement.

The Sisyphus of The New Yorker cartoonists is the Sisyphus of Henri Bergson: a kind of bureaucratic figure committed to his day-to-day work without complaint:

Take the case of a person who attends to the petty occupations of his everyday life with mathematical precision.…The laughable element consists of a certain mechanical inelasticity, just where one would expect to find the wide-awake adaptability and the living pliableness of a human being.

No one wants an angry, knowing Sisyphus.

As AIs are trained to be more thoughtful, more careful, more precise, more like the best human minds, they may become less human-like. The basic pattern recognition ability necessary for joking may get tripped up in reasoning.

The comic Sisyphus is our commitment to the premise that he doesn’t really mind. Sisyphus putting his boulder in the overhead compartment is the closest that most of us will get to really feeling his task.

If Sisyphus doesn’t mind, the question is why. Is it because the essential truth of modern human existence, as Camus points, is not minding the absurd struggle against repetitive futility? Camus imagines Sisyphus being reunited with his rock after his walk down the hill after it:

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one’s burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

This is bleak. Interesting but bleak. Not the comic Sisyphus, though Camus gets credit for opening that door. Lots has already been written about it, so I won’t add here.

The alternative is that Sisyphus doesn’t mind because the endless pushing is something he sort of or really wants to do.

If the boulder isn’t a boulder but a metaphor for pushing, carrying, struggling to do, then it changes the idea that the punishment may not be a punishment in the traditional sense. A Sisyphus figure will have an obsession to do something even if it’s not working, just because. The “extreme Sisyphus” cartoon gets at this. AI is this Sisyphus.

What if the gods condemned Sisyphus to roll a boulder up a hill for eternity because they recognized and made legible something essential about his nature, that he would continue to do what he always did, what was in his nature to do? Don’t you know people like this? Are you a person like this?

Enter Ovid

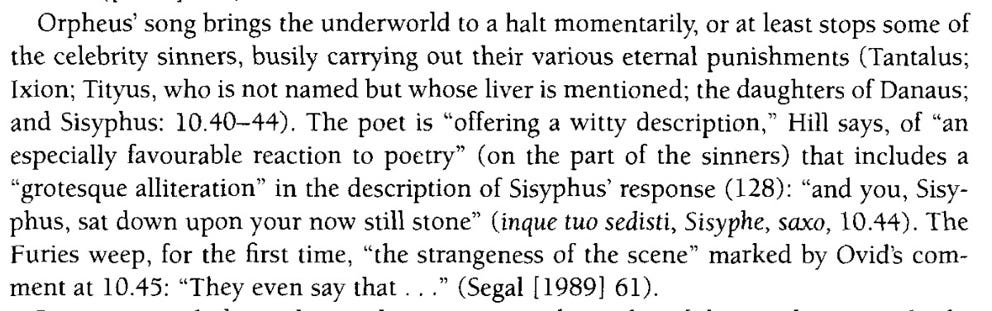

There is a thrilling scene in Book X of Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” around line 44. When Orpheus descends to the Underworld to plead for Eurydice’s return, he makes a moving plea to Hades and Persephone. There is a passage where Ovid describes various inhabitants of the Underworld being affected by Orpheus’s music: Tantalus stopped reaching for food, the Furies wept. The point of the passage is to demonstrate the impact of Orpheus’s song. At the end, the narrator says: “inque tuo sedisti, Sisyphe, saxo,” usually translated “and you sat, Sisyphus, on your rock!” It's a punchline. Not only may this be the only moment in classical literature where Sisyphus’s eternal punishment is suspended, but also the explicit pointing to “you, Sisyphus” is played for laughs. It’s really funny, in the classic Catskills manner.

As an aside, the scene in art doesn’t really capture the humor, I don’t think. But there you are, Sisyphus, sitting on your rock

The painting just above is by Jean Raoux (1709); the one above that by Frans Francken (~1600-1642). A forlorn Sisyphus appears in both, sitting on his rock in the upper background of the Raoux and the left in the Francken. He’s not the hero, he isn’t playing it for laughs. These aren’t New Yorker cartoons.

So is Ovid’s passage really supposed to be funny? The excellent scholar of ancient humor Elizabeth Archibald pointed me to two commentaries. Michael Simpson’s The Metamorphosis of Ovid (2001)…

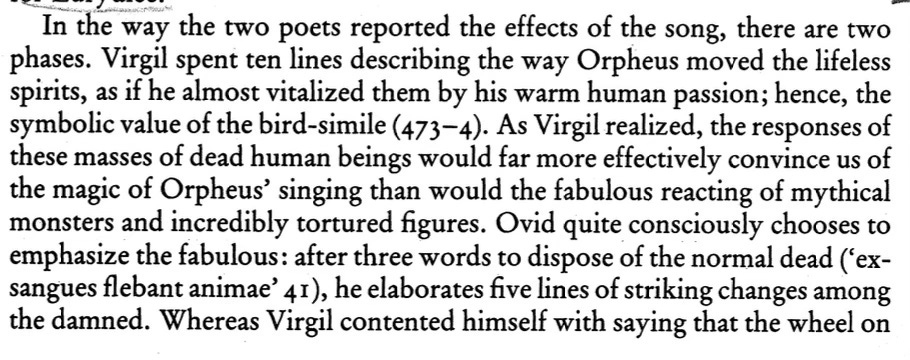

… and W.S. Anderson’s Ovid’s Metamorphosis (1978)

Ovid’s Sisyphus is not Camus’s Sisyphus, conscious of eternal failure. Ovid allows that certain natures are defined by their persistent engagement with what draws them, regardless of outcome or purpose. That Ovid’s Sisyphus stops to listen to beautiful poetry suggests his punishment isn’t all-consuming, that he can pause to appreciate art, to be moved by beauty. By sitting on his rock, he transforms what is supposedly a burden into a seat from which to appreciate beauty. For Ovid, the rock, the boulder, is Sisyphus’s companion, his constant in a changing universe. In that moment of sitting and listening, Sisyphus demonstrates a kind of mastery over his situation not through rebellion or transformation, but through simple familiarity.

We can treat the boulder as an externally imposed burden rather than an internal compulsion, the thing we are driven to do even when it defies reason or results. This way of reading Sisyphus’s shoulder to the burden makes for a more logical and a better story than divine retribution. Perhaps it takes the social media age to see Sisyphus as a mirror of human obsession, of our tendency to pursue certain truths or goals, what we cannot help but confront, as we return to particular problems, particular obsessions, particular struggles, whether or not they go viral or yield a final victory. Sisyphus labors with his burden not because he must, but because he would do nothing else.

Ovid’s image of Sisyphus sitting on his rock supports this reading.

That Sisyphus can stop and sit (of course he only does for the very best music) is not the intimacy of someone growing accustomed to a punishment, but the natural familiarity between a being and the object of its essential preoccupation. The rock is a burden but a familiar, chosen burden. It is what defines him, what he would choose even without divine intervention.

This single thrilling image of an intimate familiarity between Sisyphus and his burden changes everything for me utterly.

If Sisyphus knows the rock will always roll down again, his ability to repurpose it, to sit on it and appreciate beauty, suggests a relationship to his circumstance that goes beyond either futile struggle or heroic defiance. It suggests adaptation, familiarity, and even a kind of ownership.

But the question remains. Does Sisyphus know his efforts are futile? Does AI?

Four possibilities: 1) Sisyphus does not know the boulder will roll back down (thinking about success), 2) he knows the boulder will roll back down and strains each time anyway (conscious of futility), 3) he thinks that this time might be different (knowledge about the past and hope), and 4) he doesn’t care one way or another; the straining is the point. It’s a workout.

The first possibility is slapstick, a kind of melancholy funny for those of us watching him do the same thing over and over. This is Bergson funny. With the lightest touch (where Sisyphus is comically out of place in a loincloth or toga) it is New Yorker funny. If we imagine that he’s bureaucratically focused on his task, we can laugh at him, but there is a tinge of sadness.

The second possibility is what Camus offers: an appreciation of the proletariat Sisyphus, relatable, weary, but not funny. “If this myth is tragic, that is because its hero is conscious. Where would his torture be, indeed, if at every step the hope of succeeding upheld him?” And yet Camus’s rhetorical question opens the door to the idea of hope of success, which would change everything.

The third possibility is tragically heroic, not comic. This is the Sisyphus of the “one last heist” action movies except the heist fails. Sisyphus approaches each attempt believing that this time it might succeed. He represents the persistence of hope in the face of what others might see as inevitable failure. Perhaps the gods were not creating an eternal punishment but rather recognizing that Sisyphus would keep doing what he does precisely because the possibility of success remains open, however remote.

In this third scenario, the struggle does not represent futility, but rather those pursuits that compel continued effort despite all past failures. Maybe he will fail again, but he cannot know with absolute certainty that he will. The boulder becomes a possibility more than a burden. It is the stuff of movies: scientists pursuing seemingly impossible problems, artists attempting to capture ineffable visions, philosophers returning to fundamental questions that have resisted centuries of inquiry.

The fourth possibility is for me the most interesting.

If Sisyphus returns to the boulder and the struggle, because it is simply what he does, what he must do by his nature and perhaps with some knowledge of his nature (this is important), how wonderful for humanity. Reward isn’t the point. Different movies will be made about this figure: the philosopher who returns to an impossible question, the artist who pursues an unattainable vision, or the scientist who confronts an intractable problem, who persist not because they hope to finally, dramatically, solve or capture what eludes them, but because engaging with these challenges is intrinsic to who they are.

This is the Sisyphus more people might recognize if attention were paid to the relationship of the boulder and the burden. The boulder deserves more philosophical attention as the embodiment of compelling and impossible tasks that define a certain kind of consciousness. Maybe it’s an antisocial consciousness, maybe a little on the spectrum even. It’s lovely to think about, particularly with Ovid’s intervention. “And you sat, Sisyphus, on your rock!”

I could weep.

Simple uncertainty about the nature of the burden could transform our appreciation of Sisyphus from the figure of eternal suffering to the figure of persistent human striving divorced from success. What this means for AI’s relentless striving is up for debate.

Let’s bring the gods back in. If the point of the punishment was a kind of recognition and formalization of an essential aspect of Sisyphus’s nature — his compulsion to jailbreak regardless of outcome — does this make the myth less about divine retribution and more about the gods’ understanding of human nature itself? And what should this tell us about intelligence?

For me, the gods did not punish Sisyphus. They simply made legible what had always been true: that he would roll the rock whether they willed it or not. Sisyphus, like the best jokes, like the best obsessions, like the deepest forms of intelligence, is not about outcome. He is about the necessary return, the compulsion to push again, not because he must, but because he cannot do otherwise.

The (semi-funny) Roman poet-philosopher Lucretius (c. 99 BCE - 55 BCE) in “On the Nature of Things” (De Rerum Natura) compared ambitious politicians who strive for power and are defeated, over and over to Sisyphus. It is meant to be funny. But politicians aren’t everyday people.

Jokes about the House of Atreus or the schemes of Odysseus don’t really work — too much setup and shady family dynamics. Atlas holding up the globe for eternity? Too static. No dynamic element. No moment of hope followed by inevitable defeat. Tantalus, with his dinner forever out of reach? The frustrating modern parallels are more painful than absurd. Same with Prometheus’s daily liver-eating eagle — more grotesque than funny. Icarus’s flight too close to the sun? A perfect metaphor for hubris, but the story crashes too quickly. Narcissus gazing at his reflection? Promising in the selfie age, but not universally relatable. The Danaides, condemned to fill leaking vessels for eternity? Not well known enough, so none of the immediate recognition required for a New Yorker cartoon.

There was also this, about which there is a certain profundity:

Sisyphus took a crack at stand-up comedy.

“My life’s one big uphill battle,” he joked. “Just when my punchlines reach the peak... they roll away and I’m stuck explaining them all over again!”

At least he has an endless supply of material.

The most recent, and also trenchant, treatment of Sisyphus might be Ben Stiller's TV series "Severance."

Wonderful piece, Hollis. Thank you. I think I'll go listen to Kate Bush's "Running Up That Hill" on repeat for a bit.

One is reminded of Hopkins' poem "As kingfishers catch fire":

"...deals out that being indoors each one dwells,

Selves, goes itself; _myself_ it speaks and spells,

Crying: What I do is me, for that I came."

If your gloss on Sisyphus is correct, that's just what he's doing.