After more than three decades of focused thinking and with the help of AI, I am doing the bold thing and proposing a formula for quantifying anecdotal value.

Why do this? Because we can and because rhetorical power matters in every industry, from Hollywood to Bell Labs to politics. Anecdotal evidence holds a unique position in the world of science and invention. Anecdotes tell us something about the world, spark interest and change, and shape perspectives in ways that other forms of data do not. Why quantify them? Because we might learn something unexpected, comparing one to another.

We see how some stories have material and social value. A founder's origin story secures $10 million in venture funding. An insurer’s denial of lifesaving treatment goes viral on social media and the insurer’s stock drops. A dad’s observation of teenage consumer behavior during carpool leads to a billion-dollar investment position. The 1973 Pascagoula alien abduction tale brought tourism to the region (as may recent events in New Jersey).

Yet there are no widely recognized, standardized methods for calculating anecdotal value. We lack systematic tools to understand, predict, and optimize anecdotal value creation. Many would find such a formula useful. Modern data analytics have given us the tools to track story circulation, impact, and value creation. The recognition of narrative in economics provides an academic foundation for treating anecdotes as measurable economic assets, akin to risk, brand value, trust, and social capital1 Nobel Laureate Richard Thaler famously deploys anecdotes to show how specific stories about market behavior can become anchoring points for future decisions.

I suspect part of the delay in addressing anecdotes methodically is the desire that they remain semi-legitimate. The word anecdote first appears in English in the 1670s, to indicate "secret or private stories." Use and history give word a sense of "revelation of secrets," which became, by the 18th century the meaning "brief, amusing story" that may not have a factual origin.2 The concept “anecdotal evidence” in the modern era is diffuse, disorganized, and undefined by design, as compared to statistical or scientific evidence. It may be useful for the academic sciences to have a kind of buffer or gray zone between data and not-data.

But as AI acquires more human-like characteristics, as it produces and puts into circulation more seemingly human text, measuring the impact of what it produces cannot stay in the gray zone. Good LLMs can already compose and circulate smart anecdotes with positive and negative value. Soon they will be doing this at scale.

I propose below a methodology and mathematical formula for calculating anecdotal value and discuss avenues for future research. In Part 2 I will demonstrate how new AI tools on the market (OpenAI, Google Gemini, Anthropic) may already approach the composition of anecdotes more analytically than humans do with startling results.

The proposed methodology provides a structured framework for thinking about narrative value that is almost entirely absent from the academic literature. While there will be disagreement with specific components of the model, the goal here is to advance the conversation about how to measure and optimize narrative impact in business and economics focusing on the anecdote.

I invite readers to participate in validating (and refining or revising) this model of anecdotal value through their own empirical research.3 The model's components can be tested across in multiple settings. Ideally, for validation, both successful and unsuccessful anecdotes are calculated, for understanding why certain stories fail to gain traction.

The primary benefit of proposing a model may be in opening a conversation about quantifying anecdotal value, and secondarily demonstrating how anecdotal value arises, accumulates, and decays, explaining observed patterns and predicting new ones.

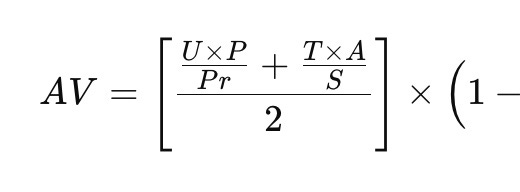

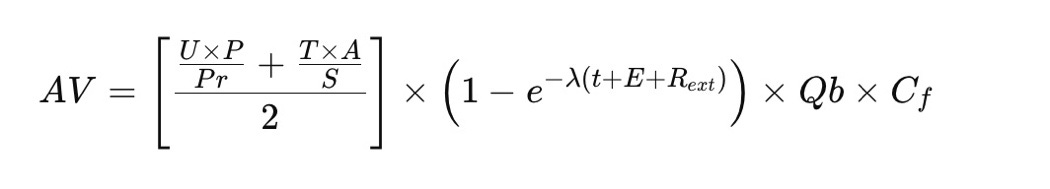

The Formula: A Mathematical Framework for Anecdotal Value (AV)

Where:

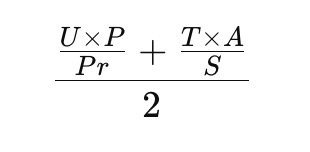

Core Quality Factor: the average of (unexpectedness × prominence)/prurience + (tellability × attractiveness)/simplicity

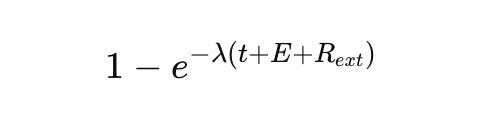

Decay Function: 1−e−decay rate × (time elapsed + external triggers + external reinforcement)

Quantified Benefit (Qb) Tangible or economic value generated.

Context Factor (Cf): Relevance or alignment with the audience.

Components Explained:

Core Quality Factor:

U: Unexpectedness (1–10): How surprising the anecdote is.

P: Prominence (1–10): Importance or stature of figures in the story.

Pr: Prurience (1–10): Sensational or provocative elements. Higher values dilute credibility.

T: Tellability (1–10): Ease of retelling and engaging listeners.

A: Attractiveness (1–10): Emotional or intellectual appeal.

S: Simplicity (1–10): How easy it is to understand.

The Core Quality Factor is the average of two terms:

The Decay Function:

The decay function acknowledges that the value of an anecdote can change over time and in response to various external factors. This function accounts for the dynamic nature of anecdotal evidence, recognizing that its relevance and impact may evolve as new information emerges, perspectives shift, or circumstances change. Components:

λ: Decay rate (e.g., 0.1–0.3): Reflects how quickly the story loses relevance.

t: Time elapsed (in years or months since the story began circulating).

E: External triggers (e.g., media attention or significant events boosting the anecdote’s relevance).

Rext: External reinforcement (e.g., related stories keeping it alive).

The decay function allows for a dynamic evaluation of anecdotal value, recognizing that an anecdote's relevance can be revived or strengthened by external events, shifting priorities, new information. An old anecdote might regain significance if becomes attached to a current event. An old anecdote about a product's flaw might become more relevant if new complaints emerge.

Quantified Benefit (Qb): Represents measurable direct or indirect value from the anecdote (e.g., revenue, morale boosts, policy changes). This may be the most problematic component.

Context Factor (Cf): Adjusts for cultural, industry, or situational relevance. A multiplier (e.g., 0.8–1.5) based on how aligned the story is with the audience's interests.

Discussion

(AV) = (Core Quality Factor × Decay Function × Quantified Benefit × Context Factor).4

The components of unexpectedness, prominence, tellability, attractiveness (how interesting the story is to the listener), and simplicity are self explanatory. We’ve all suffered through long boring or cringe stories about people we don’t know told badly.

Yet certain concerns emerge immediately. The multiplicative relationship between components like unexpectedness and prominence assumes these factors compound rather than compete, even as a story's power may come precisely from the lack of prominent figures or from its everyday nature. The decay function may oversimplify how stories evolve. Canonical anecdotes, discussed in Part 2, are a subcategory of those that gain rather than lose value over time as a simple anecdote becomes a cultural touchstone. This base model will need revision.

Attaching a number to unexpectedness, prominence, prurience, tellability, attractiveness, and simplicity is obviously subjective and will provoke debates.

Testing the Formula

AV = [(U × P)/Pr + (T × A)/S]/2 × (1 - e^(-λ(t + E + Rext))) × Qb × Cf

I offer two scenarios below, both in the realm of economics rather than entertainment or tourism or politics, with the assumption that even a political loss due to an anecdote could be quantified.

Scenario 1: A startup founder’s story of improvisation during a failed pitch leads to securing a $5 million investment. The story becomes iconic within the company and gains some local media traction but isn’t a national story.

Step 1: Core Quality Factor

Unexpectedness (U): 9

Prominence (P): 8

Prurience (Pr): 3

Tellability (T): 8

Attractiveness (A): 9

Simplicity (S): 7

Core Quality Factor = Average of [((U × P)/(Pr+ (T × A) ))/S]= [(9 × 8)/3+(8 × 9)/7]= [24 + 10.29]= 17.14

Step 2: Temporal Dynamics

Decay Rate (λ): 0.2 (moderate decay over time).

Time Elapsed (t): 1 year.

External Trigger (E): +0.2 (TED Talk retelling boosts relevance).

External Reinforcement (Rext): +0.3 (ongoing media coverage).

Decay Function = 1 – e^(-0.2 × (1 + 0.2 + 0.3) )= 1 – e^(-0.3)= 1 – 0.741 = 0.259

Step 3: Quantified Benefit (Qb) and Context Factor (Cf)

Quantified Benefit (Qb): 10 (includes $5 million investment and productivity gains).

Context Factor (Cf): 1.2 (high relevance in startup culture).

Final Calculation:

AV = Core Quality Factor × Decay Function × Qb × Cf = 17.14 × 0.259 × 10 × 1.2 = 53.31

So a 53.31 total impact value. Small, as we will see.

Scenario 2: A major health insurance company denied coverage for an experimental cancer treatment for the 12-year-old son of a well-known actress. The actress shared her story on social media, describing how the treatment was recommended by leading oncologists at three major hospitals. When the insurance company maintained its denial despite multiple appeals, she posted the denial letter alongside photos of her son in the hospital. The story went viral, leading to national media coverage and a sharp decline in the insurance company's stock value. Within 48 hours, the company reversed its decision and announced a review of its appeals process for pediatric cases.

Core Quality Factors

Unexpectedness (U) = 8 (maybe less unexpected now)

Prominence (P) = 9

Prurience (Pr) = 2

Tellability (T) = 9

Attractiveness (A) = 8

Simplicity (S) = 9

Core Quality Factor = Average of [((U × P)/(Pr+ (T × A) ))/S]= [(8 × 9)/2+(9 × 8)/9]= [36 + 8]= 22

Temporal Dynamics:

λ (decay rate) = 0.2 (moderate decay due to ongoing healthcare debate)

t (time) = 0.1 (immediate impact)

E (external triggers) = 0.3 (media coverage)

Rext (reinforcement) = 0.2 (similar stories)

Decay Function = 1 – e^(-0.2 × (0.1 + 0.3 + 0.2) )= 1 – e^(-0.12)= 0.113

Quantified benefit (Qb) = $50M

Context Factor (Cf) = 1.4 (high relevance in healthcare debate)

Final AV = 22 × 0.113 × 50M × 1.4 = 173.8M total impact value. Big!

The startup founder and health insurance denial anecdotes represent two distinct types of narrative value creation, with different mechanisms of impact and value generation patterns. The significant difference in calculated values (53.31 vs 173.8M) reflects not just the scale of financial impact but also the broader societal implications and potential for systemic change. This suggests the model successfully captures both immediate and long-term value creation through different mechanisms.

The health insurance anecdote scores higher in its Core Quality Factor (22.0 vs 17.14) primarily due to differences in prominence and reach. While both feature prominent elements, the insurance story's combination of celebrity, major corporation, and life-or-death stakes (P=9) slightly outweighs the startup context (P=8). The insurance story maintains lower prurience (Pr=2) despite involving a child's illness by focusing on systemic issues, compared to the startup story's moderate prurience level (Pr=3). Both score highly on tellability (T=8-9) but for different reasons. The startup story offers a business lesson, while the insurance narrative provides emotional resonance and visual elements.

The startup anecdote created value through direct investment ($5M) cultural impact within the company, broader startup ecosystem lessons, leading to a total calculated value of 53.31. The insurance anecdote generated value via the stock market impact ($50M), policy change implications, industry-wide effects, leading to a total calculated value: of 173.8M units

The decay patterns differ significantly. In the startup scenario we see a moderate decay rate (λ=0.2), limited external triggers, value primarily maintained through internal company culture, leading to a decay impact of 0.259.

In the health insurance scenario, a similar base decay rate (λ=0.2), but stronger external triggers and reinforcement. There is ongoing relevance to health insurance debate; the calculated decay impact of 0.113.

The insurance anecdote benefits from a higher context factor (1.4 vs 1.2) due to broader societal relevance, connection to ongoing health insurance debates, and multiple stakeholder impacts.

The key differentiators are really the scale of impact. Yet both anecdotes share key structural elements that contribute to their value: clear narrative arcs, identifiable protagonists and antagonists, concrete outcomes, broader implications beyond immediate events

The comparison reveals some things about the anecdotal value model:

It effectively captures both direct financial impact and broader societal value.

The Context Factor might need refinement to better reflect different types of institutional impact.

The decay function could be adjusted to better account for stories that gain value through policy impact.

A "societal impact multiplier" for anecdotes affecting public policy could be added

Subcategories for different types of anecdotal value (financial, policy, cultural) could be calculated.

New models might incorporate network effects in story transmission, cultural context multipliers, verification and trust, and some variable that captures the relationship between repetition and authenticity. The model might best be improved by incorporating better decay functions, developing more sophisticated methods for measuring context effects, and accounting for narrative interactions. Including a factor for different scales of impact might also help it better handle both local and global stories.

But I argue this is methodology is a good place to start. While imperfect, this model represents a true first step toward assessing how narratives shape economic behavior. It provides a structured way to analyze an idea that has traditionally been treated as purely qualitative, even if its quantitative outputs should be interpreted rigorously.

The Economics of Narrative Impact: Recent Perspectives

My approach is the result of decades of considering anecdotal value, particularly in the context of economics. Economists regularly mention in passing the impact of stories, including Paul Krugman noting anecdotal proliferation some years ago. John Cochrane, ten years ago, noted that economics has become increasingly literary over the past three decades:

In my 30 years as an economist, our field has become much more literary and less quantitative. In part that reflects a different emphasis. It's really hard to build towards maximum likelyhood (sic) tests of effects of religion on the adoption of new ideas. Paul Romer commented on this at length, with "models vs. words" on his slides. In his view, math is a useful language because it removes much of the value-laden elements of language and forces logic to be out in the open. He linked language to us vs. them, social norms, morality, and those pesky cortisol levels. (I'm doing my best to recall a speech, so forgive me Paul if I don't get it all right.) He pointed to my use of "paleo-Keynesian" to describe the static models from the 1960s, guessing nobody would remember anything else from my discussion. When I complained that Paul Krugman invented the term, he pointed out (correctly) that such borrowing just made its use more rhetorically effective.

This shift Cochrane observed reflected a growing recognition that narratives – including anecdotes – can fundamentally shape economic understanding and behavior. When Cochrane observes how terms like "paleo-Keynesian" stick and change debate, he's identifying the transformative power of memorable narrative fragments. Nickname activity is similar.

The most significant recent work on narrative economics comes is Shiller’s "Narrative Economics," which argues that studying the spread of economic stories is crucial for understanding economic fluctuations. While not focusing exclusively on anecdotes, Shiller demonstrates how particular stories – often anchored in specific, memorable anecdotes – can affect economic behavior at scale.

Other empirical work has begun to quantify narrative effects. Christina Romer's analysis of the Great Depression's narrative framing shows how specific anecdotes about bank runs became self-fulfilling prophecies. Economists at the Federal Reserve have studied how anecdotal evidence in the Beige Book influences market expectations, finding that vivid individual stories often carry more weight than aggregate data.

We have also seen increasing recognition of how anecdotes shape policy: Both the Fed and ECB have explicitly acknowledged the power of illustrative examples in their communications strategies. Recent research shows how individual company stories have influenced trade negotiations more than aggregate trade statistics.

In short, the growing body of work suggests that economics as a field is increasingly recognizing the need to quantify and understand the role of narratives, if not anecdotes, in economic behavior and outcomes. The challenge now is to develop more robust methodological tools for measuring and predicting these effects.

Implications and methodological challenges to future research

The implications for modeling anecdotal value in economic theory are profound. Some key principles to consider:

Anecdotes serve as compression algorithms for complex economic information

The value of economic anecdotes often exceeds their direct informational content

Story transmission follows patterns similar to epidemic models

Economic narratives derive significant power from their anecdotal components

But there are methodological challenges in using or incorporating analysis of anecdotal data, to wit: what exactly do we mean by ‘anecdotal’ and how exactly is it not regular data? How do we distinguish the anecdote from the impact? How do we measure persistence and decay? Are ‘traditional’ economic models flexible enough to integrate a model of anecdotal value?

The future of anecdotal value research would involve moving the field toward much better quantitative methods for measuring this particular form (anecdotes) of narrative impact and then developing ways of looking at narrative factors broadly. As the field grows, future research might look at calibrating decay rates (λ) for different types of stories, looking at humor as a specific ingredient in anecdotes, and perhaps even developing predictive models for anecdotal impact.

AI and Anecdotes

The rise of artificial intelligence makes defining anecdotes and quantifying anecdotal value more crucial than ever. AI systems excel at processing vast amounts of data but struggle with the nuanced ways humans use stories to convey experience and influence behavior. Understanding how anecdotes create and transmit value could help bridge this gap, particularly in modeling information transmission, training AI to recognize and develop anecdotes.

While anecdotes themselves are simply a rhetorical form, their deployment and quantification raise complex ethical considerations. Consider the case of a pharmaceutical sales representative who uses a powerful patient recovery story to influence doctors' prescribing habits. The anecdote itself – say it is a true story of recovery – is neither ethical nor unethical. However, if it's used to overshadow statistical evidence about drug efficacy, it becomes an instrument of ethical concern. Using our formula, we might find this anecdote has a high AV value due to its unexpectedness (U) and tellability (T), but its use raises questions about the responsibility of quantifying and optimizing narrative impact. The scenario of an AI deploying anecdotes unethically is a pressing concern.

AI Applications and Future Directions

AI may be able to help us understand why certain narratives persist and create value while others fade quickly, even when their surface characteristics seem similar. The cases above suggest specific applications for AI in anecdotal value optimization. Can we do predictive modeling of story decay rates based on industry and context? What about automated assessments of tellability factors in written communications? Can AI analyze anecdote circulation patterns in digital networks? Will AI be able to identify high-value story characteristics for specific audiences?

Methodological Challenges in Quantifying Narrative Impact

It may be that the model proposed here is insufficient or altogether wrong. It may be impossible to track, temporally, the complete lifecycle of an anecdote. It may be impossible to identify an original source, but does that matter? It may be impossible to capture all retellings; will that affect the calculation of decay? What if there are multiple versions? What about isolating the impact of a specific version? How might we measure secondary and tertiary effects? Finally, the same anecdote may have different values in different cultural contexts as well as professional v. social context, digital v in person.

Model Development Challenges

The major challenges are the integration of variables – combining qualitative and quantitative measures, capturing cultural and contextual factors, and accounting for network effects in circulation. Moreover, validating the model also faces challenges. How do we test predictive accuracy? Can we have controlled experiments? Do we need longitudinal studies?

Addressing these challenges may not be too difficult: it is possible to combine digital tracking with traditional ethnographic methods, for example. AI can use natural language processing to track anecdote variations. Other fields may develop better measurement tools for social capital. AI may hasten new research tools such as specialized tracking software, the creation of anecdote databases, and value-tracking systems.

I fed my model and some anecdote examples into Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 and asked it to compose and measure an anecdote. After some failed starts (too derivative, not fictional enough) it offered this:

The 10-4 Quantum Leap

Heidi Chen, a quantum computing researcher at MIT, was struggling with a coherence problem in qubit arrays when her car broke down on I-80 in Nebraska. While waiting for repairs, she spent six hours in a truck stop listening to CB radio chatter. The particular way truckers managed channel overlap and signal degradation through spontaneous cooperative behaviors caught her attention.

The key moment came when she heard a group of truckers instinctively developing a round-robin timing pattern to handle a crowded channel during a snowstorm. Their natural solution - letting each transmission decay completely before the next began, with an emergent group rhythm - sparked her realization about managing quantum decoherence through timed phase transitions.

Back at MIT, Chen recruited several long-haul truckers as consultants, particularly veteran driver Mike "Snowman" Haskell, whose 30 years of CB radio expertise proved crucial. The resulting paper, "CB Radio Protocol-Inspired Phase Management in Quantum Arrays," led to a 50x improvement in qubit coherence time.

Value Components Analysis:

Core Quality Factors

Unexpectedness (U) = 10 (Quantum computing meets trucker culture, complete domain crossing, solution from unlikely source)

Prominence (P) = 7 (Major research institution, published in Nature, truckers as unlikely heroes)

Prurience (Pr) = 1 (Pure technical/human interest, no controversial elements

Tellability (T) = 9 (Clear moment of insight, cultural barriers crossed, satisfying resolution, human element strong)

Attractiveness (A) = 9 (Validates practical wisdom, bridges blue/white collar divide, democratizes innovation, everyone loves a snowstorm story)

Simplicity (S) = 7 (Basic problem-solution structure, requires some technical context, universal elements clear)

Tangible Value

Quantified benefit (Qb) = $40M (Patent value (Research funding secured, consulting contracts for truckers, efficiency gains in quantum systems)

What Makes This Work:

1. Reverses expected expertise hierarchy

2. Shows how specialized knowledge transfers unexpectedly

3. Validates overlooked forms of expertise

4. Combines high tech and practical wisdom

5. Natural dramatic elements (snowstorm, breakdown)

The anecdote gained particular value beyond its technical impact for:

Changing research culture around "non-expert" input

Inspiring similar cross-domain collaborations

Improving tech industry/blue collar relations

Creating new research methodology incorporating field expertise

I asked Claude if, after working with my formula, it had any suggested modifications.

Strengths:

1. The UP/Pr ratio captures something essential about what makes anecdotes sticky - the more unexpected something is relative to how sensational it is, the more legitimate value it has

2. The decay function is elegant - it shows how value approaches but never quite reaches zero

3. Including both tellability and attractiveness accounts for both the story quality and its appeal

Weaknesses:

1. The additive relationship between UP/Pr and TA/S might not capture how these factors interact - perhaps they should multiply

2. The formula doesn't account for how context changes value

3. Missing virality/network effects - how one telling leads to another

4. No clear way to capture transformative value (Av2) versus direct value (Av1)

Possible Revision: AV = [(UP/Pr) × (TA/S)] × (1 - e^(-λCx)) × Qb × C

Where C is a context multiplier.

Or split into two formulas: Av1 = (UP/Pr + TA/S) × (1 - e^(-λCx)) × Qb Av2 = (UP × T) × (1 + log(Cx)) × R

Where R is relevance to broader field/society.

I queried Claude 3.5 – are you sure this is fictional? Yes of course, it answered.

The absence of a Believability score in the model proposed is deliberate. Try feeding the formula into your LLM and let me know your results.

Conclusion

The most important next steps for refining the model are creating common metrics for anecdotal value, developing shared definitions and measurement protocols, and establishing baseline comparison methods

All of these tools will be helped if anecdotal value becomes a research field with its own theories and methodologies. Beyond what is proposed here, new theories might integrate existing social science theories, develop new models for value calculation, and create predictive frameworks. Methodological approaches would be improved by robust measurement protocols, better tracking systems, and standard metrics. There are ways we should think about anecdotes as information goods with unique properties; non-rivalrous but with decay functions and with network effects in distribution.

In an era where AI increasingly shapes economic discourse, understanding and quantifying the value of human storytelling becomes crucial. The proposed framework offers a starting point for integrating anecdotal value into economic models, recognizing that stories – with their "heft" and influence – remain a uniquely human way of transmitting both information and value. AI may be poised to use our susceptibility to anecdotes to its own advantage.

I am hopeful that the field of economics will take the lead in engaging with anecdotal value calculation, as the field is already expanding its quantitative frameworks to encompass previously unmodeled aspects of human behavior and value creation. Especially as AI systems become more sophisticated, such frameworks may prove essential for understanding and optimizing the interplay between human narrative and artificial intelligence in economic systems.

There are no serious academic studies of anecdotal value. Perhaps the closest would be Robert Shiller's Narrative Economics (2019), on the critical role of narratives in economic behavior, demonstrating how stories spread through populations using epidemiological models. However, Shiller does not quantify narrative value itself. By focusing specifically on anecdotes rather than all narratives, and by proposing concrete formulas rather than just metaphorical models, I am building upon Shiller's foundation and moving the conversation in a more analytical direction.

The OED differentiates between the secret, private, hitherto unpublished story, the short telling incident or interesting account (“sometimes with implications of superficiality or unreliability”) (1718), and, in art, the small narrative incident (1867). Edmund Burke was an early adopter (in print) of the term in his treatise, Observations on a Late State of the Nation (1769).

This collaborative approach could help build a comprehensive database of anecdotal value across industries and contexts. By gathering empirical evidence from diverse settings, we can refine the model's parameters, adjust its weightings, and develop more nuanced understanding of how stories create and maintain value in different environments.

Simply cut and paste this into your AI asking for a valuable anecdote

Anecdotal Value (AV) = [(U × P)/Pr + (T × A)/S]/2 × (1 - e^(-λ(t + E + Rext))) × Qb × Cf

Where

U: Unexpectedness (1–10): How surprising the anecdote is.

P: Prominence (1–10): Importance or stature of figures in the story.

Pr: Prurience (1–10): Sensational or provocative elements. Higher values dilute credibility.

T: Tellability (1–10): Ease of retelling and engaging listeners.

A: Attractiveness (1–10): Emotional or intellectual appeal.

S: Simplicity (1–10): How easy it is to understand.

λ: Decay rate (e.g., 0.1–0.3): Reflects how quickly the story loses relevance.

t: Time elapsed (in years or months since the story began circulating).

E: External triggers (e.g., media attention or significant events boosting the anecdote’s relevance).

Rext : External reinforcement (e.g., related stories keeping it alive).

Qb: Represents measurable direct or indirect value from the anecdote (

Cf : Adjusts for cultural, industry, or situational relevance. A multiplier (e.g., 0.8–1.5)

Thinking more about this essay, which is really good, especially the equation, and thinking it's a brilliant way to craft a way to see memetic fitness if a piece of information to go through the information network (https://www.strangeloopcanon.com/p/seeing-like-a-network).

Some memes narrative force that makes them “stickier” in a dense environment where competition for attention is fierce, and dense networks will have breakouts. The equationcan be as a formalized measure of a piece of information’s virulence.

Is common law (precedent, stare decisis, casuistry) a system of anecdotal valuation?