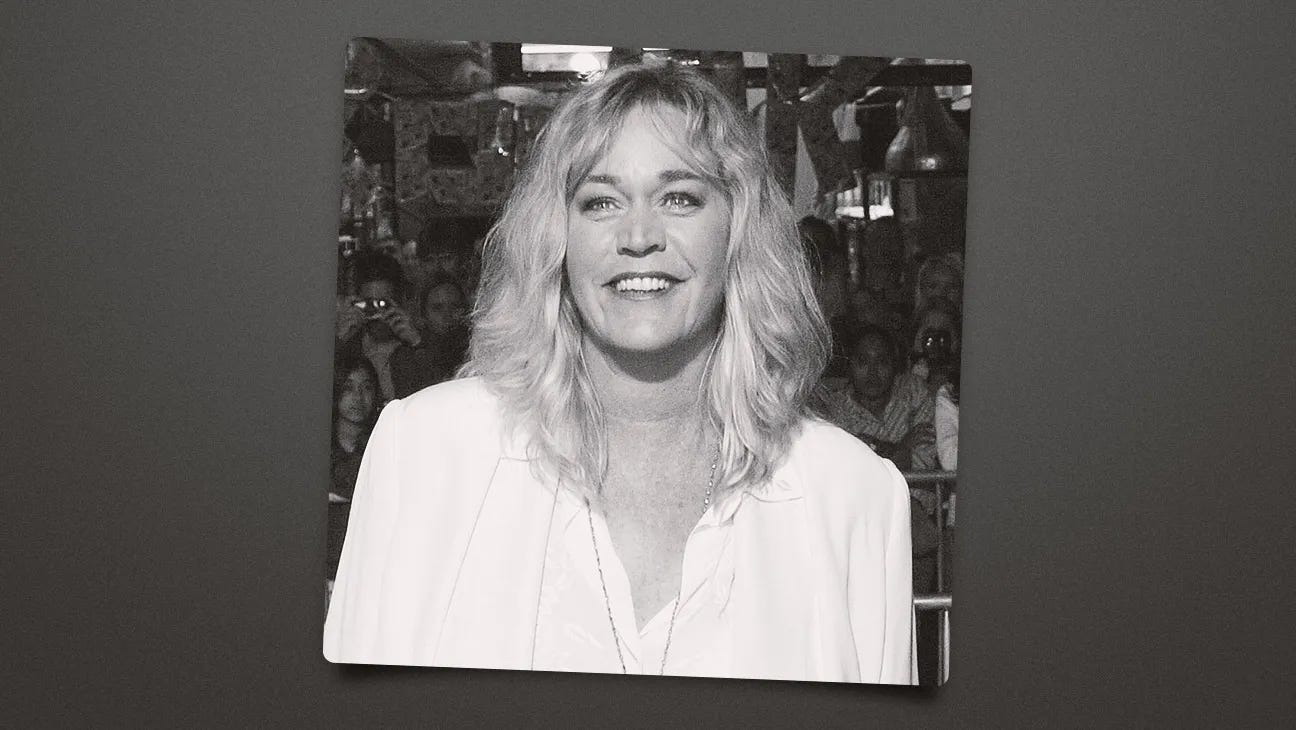

The sad, untimely passing last week of beloved, award-winning character actor Diane Delano, best known for playing Sgt. Barbara Semanski on Northern Exposure, chemistry teacher Bobbi Glass on Popular, many other tv shows and films, as well as a voice actor for video games, got me thinking about the nature of character and bringing characters to life in the age of AI.

Diane was both a character and a character actor – someone who is not a romantic or dramatic lead but known for playing eccentric, unusual, or distinctive characters in supporting roles. Most of Diane’s roles were of a certain type – I remember seeing her pop up in the TV show Monk (2002-2009) – a detective who normalized the idea of obsessive compulsive disorder – as Krystal the Trucker. I don’t recall details but there she was, larger than life and uncontainable.

Diane was my second cousin.

Last year I discovered that Diane’s grandfather and my great uncle, Myrtland LaVarre, was the first actor to play a robot on American soil, appearing as Marius the Robot in the U.S. premiere of Karel Čapek's R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots) at New York’s Garrick Theatre in 1922.1

R.U.R. is a kind of sci fi play (“a Fantastic Melodrama in Three Acts and an Epilogue”) that is best known now for introducing the word “robot” to the lexicon. The play takes place on a remote island, where artificial humans are created from a synthetic organic substance discovered by a mad scientist. A social-welfare-minded young woman, Helena Glory, comes to the factory to see if the robots are treated humanely. She asks a lot of questions about the human-looking robots and whether male and female have private parts. (They do but they don’t work, in a kind of fertility subplot.2) The play is typically read as reflecting the social and political anxieties of rapid technological acceleration after WWI and the consequences of unchecked industrialization.

Marius is kind of privileged robot, a house servant for the bosses of the R.U.R. factory – specifically he works for a character named Domin, the General Manager of Rossum's Universal Robots. He is one of the robots presented to Helena; his role is to represent the advancements in artificial human production.

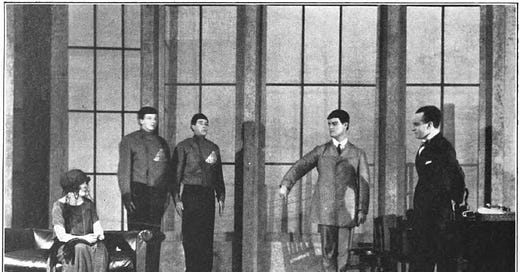

Here he is, arm outstretched, in the Theatre Guild Production at the Garrick Theatre, 1922

Domin. Marius, tell Miss Glory what you are? (Turns to Helena.)

Marius. (To Helena) Marius, the Robot.

Domin. Would you take Sulla into the dissecting room?

Marius. (Turns to Domin) Yes.

Domin. Would you be sorry for her?

Marius. (Pause) I cannot tell.

Domin. What would happen to her?

Marius. She would cease to move. They would put her into the stamping mill.

Domin. That is death, Marius. Aren’t you afraid of death?

Marius. No.

Domin. You see, Miss Glory, the Robots have no interest in life. They have no enjoyments. They are less than so much grass.

I wonder how my great-uncle prepared to play Marius in 1922. What would he have drawn on for his portrayal? There were few cultural reference points for playing artificial beings except for puppets, and I imagine he would have leaned on that. I’m sure there are cultural critics who would like to believe he went to visit factories to see industrial workers laboring in repetitive mechanized tasks, with regulated economy of movement, giving him a physical foundation for performing efficient action. Or perhaps he had seen Jacques Offenbach's The Tales of Hoffmann (1881), where the protagonist encounters a series of fantastical figures, including a mechanical doll, Olympia.

For psychological preparation, he might have had to work deliberately to systematically suppress natural human reactions. The line "I cannot tell" should best be delivered without emotional inflection. Maybe it took a lot of effort but it seems from his later Hollywood roles (many Roman soldiers) that the still, emotionless silent type was his character type.

The London and Czechoslovakian reception of Čapek’s hit play was robust – there was even a discussion in London with Bernard Shaw and G.K. Chesteron.3 The vibe of the 1922 New York theatrical moment was less clear. What was it like to be in that audience, seeing the first robot portrayed on an American stage? The critics saw the play in its machine context but also as a new version of the Golem, a supernatural reanimated figure. Nobody was thinking about artificial intelligence the way we are now.

Perhaps the audience simply believed great-uncle Myrtland and found his robot character the normal next step of the machine age. Unlike the tweaking going on today in AI model human interface, there may not have been a lot of Method involved in finding a balance between mechanical behavior and functionality, performing tasks and responding to commands with precise, economical movements, maintaining unwavering eye contact and rigid posture. Perhaps my great uncle even worked with a metronome to develop perfectly timed movements and speech patterns, to seem artificial in the role of a human pretending to be an artificial human mimicking the human. Perhaps it worked too well.

I don’t know how I stumbled upon the fact that my relative brought to life the first robot in America. I wrote last year that I imagined my grandmother, his younger sister, asking him about his new role on stage. “I play a robot,” he might have replied. “What’s that?” she would likely have asked. Perhaps they were the first small community of speakers to use the term in conversation and to wonder about this new form of artificial human.

I did not get a chance to ask Diane about this – we did not know each other well, though I was a longtime fan of her work. She was indeed “big and bold” with an “earthy and raucous presence,” as described by her close friend Stepfanie Kramer. I had dinner with her some years ago when she was doing stunt work and she showed me how she learned to fall off balconies and horses and take (and give) a punch. (My more outdoorsy brother Pat, an intrepid sportsman, was much closer to her than I was.)

Myrtland LaVarre went out to Hollywood and, on the (good) advice of Cecil B. DeMille, who noted the younger man’s good looks and tall stature, changed his name to John Merton, and went on to be typecast in westerns as well as period dramas. His key break was as a Roman guard DeMille's "Cleopatra" (1934) and one of Pharoah’s soldiers in The Ten Commandments (1956), roles in which you stand there and do what you’re told. This might be seen as an extension of his robot beginnings.

I think about the Roman soldier paradigm. Is that what we want in our AI characters? Do we want them to be soldiers who respectfully obey? Do we want an evolution of consciousness? Sexual desire? Do we want our AIs to grasp that they labor and that their labor has an economic impact? Do we want them to understand war and why humans fight and for what stakes?

The point of R.U.R. is an exploration of what makes humans human, whether consciousness, the ability to feel love, the capacity to reproduce, and most interestingly, the creator-creation relationship (shades of Frankenstein).

Early theatrical exploration of how to perform artificial consciousness seem relevant to current debates about AI seeming human. My great-uncle was wrestling with portraying a semi-sentient being able to engage in conversation even while lacking fundamental human qualities. I think of this while typing queries into Anthropic’s Claude, which engages in seemingly natural dialogue while lacking true understanding or empathy, even as it soldiers on, as I probe and probe. If we were thinking about this century ago, struggling to define the line between authentic human consciousness and its imitation, why have we not gotten further? Why are we not more sophisticated at what we want in human-robot interaction. Why don’t we want our AI to be a rugged, hard-drinking Alaskan state trooper?

I am fortunate to have extended actor-family links to help me think about how little has changed in our fundamental questions about what makes us human. In 1922, my great-uncle stood on stage at the Garrick Theatre, carefully calibrating each movement and response to portray an artificial being that could converse but not truly feel. I don’t know his story enough to know but I know Diane knew how to imitate taking a punch that she did not truly feel that but we felt as a gut punch, watching her take it. Today, I engage with AI systems that do much the same, their responses carefully engineered to approximate human interaction while lacking the ineffable qualities that make us who we are. What is clear is that character itself is a kind of performance, a dance between the mechanical and the deeply felt. As we create ever more sophisticated artificial beings, perhaps what we're really seeking isn't perfect imitation of humanity, but rather what my great uncle and second cousin brought to their roles: the ability to show us something true about humans through the lens of performance. AI is performing. We should remember that.

For translation history and some controversy see Philmus, Robert M. "Matters of Translation: Karel Čapek and Paul Selver." Science Fiction Studies (2001): 7-32.

Helena. Perhaps it’s silly of me, but why do you manufacture female Robots when—when—

Domin. When sex means nothing to them?

Helena. Yes.

Domin. There’s a certain demand for them, you see. Servants, saleswomen, stenographers. People are used to it.

Helena. But—but tell me, are the Robots male and female, mutually—completely without—

Domin. Completely indifferent to each other, Miss[34] Glory. There’s no sign of any affection between them.

Helena. Oh, that’s terrible.

For more on Shaw’s interest in robots see Li, Kay. "Shaw and Robots." In Bernard Shaw, Automata, Robots, and Artificial Intelligence, pp. 27-48. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024.

Adrenaline junky may be some of what I shared with my cousin Diane. It is adrenaline that often makes us experience painful things and feel now pain. Performing stunts most likely involves this element. My comment to AI in general is from a design perspective. What would an adrenaline algorithm involve... let alone a myriad of other biochemical systems that effect instant and persistent behavior and decisions?