Two hundred years ago, Washington Irving created two of American literature's most popular stories from what seem like simple anecdotes: a man who napped through the American Revolution, and a man who pranked his schoolteacher rival with a horse and a pumpkin. Anecdotal value belongs in the realm of romance and politics, as well as economics. Many are about character, and change your thinking once you’ve heard them.

Since my post on quantifying Anecdotal Value, my inbox has been full of emails from old friends with whom I debated anecdotal value over the years. Friends from The New Yorker are most vocal – why didn’t I mention the genesis of my interest, which was our shared experience being in our 20s in New York in the 1980s, in those Jay McInerney Tama Janowitz days, long before the internet or Carrie Bradshaw, when chance subway and elevator encounters, fixups, and slips of paper with scrawled phone numbers that led to dates always, always had anecdotal value.

Most of these were family friendly, like watching an elderly Charles Addams in the elevator, overhearing someone tell someone else they were going to Death Valley for the holidays, lean forward and say, “I’ve always wanted to go there.” Or Harold Brodkey, before he died, picking on our end-of-day plans-making slang as “utterly incomprehensible.” (The elevators at the old offices at W 44th Street were very slow.) Or the way we’d all press our backs against the wall if Ved Mehta entered. (We’d heard he’d sent an intern out of the room because he could smell her menstruating.)

(That last one is the origin of my addition of a Prurience score to calculating anecdotal value. The best anecdotes we could tell in mixed company.)

I mention this literary history because Isaac D’Israeli (1766-1848) who was, as the historian Cecil Roth describes, “in all probability the first European Jew since the Renaissance, if one excepts Moses Mendelssohn in Germany... who had ostensibly reached the front rank in what was then termed the Republic of Letters,” was best known then as the author of a 5-volume defense of Charles I, but also spent a decades of his life writing and revising (14 editions!) a 5-volume series, Curiosities of Literature, which includes a Dissertation on Anecdotes (1793).

(He was also known for quitting Judaism after a quarrel with his synagogue, and who hasn’t done that.)

Isaac is probably best known now as the father of British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881), whose Tory leadership has been in recent years touted as a model for the GOP.

What does it mean that this most interesting Conservative PM was raised by a father who loved anecdotes?

Some bits from his father’s Dissertation on Anecdotes:

“[Samuel] Johnson has defined the word, by saying that ‘It is now used after the French for biographical incident; a minute passage of private life.’ This confines its signification merely to biography; but anecdotes are susceptible of a more enlarged application. The word is more justly defined in the Cyclopaedia, ‘a term which (now) denotes a relation ‘of detached and interesting particular.’ We give anecdotes of the art as well as the Artist; of the war as well as the General; of the nation as well as of the Monarch.

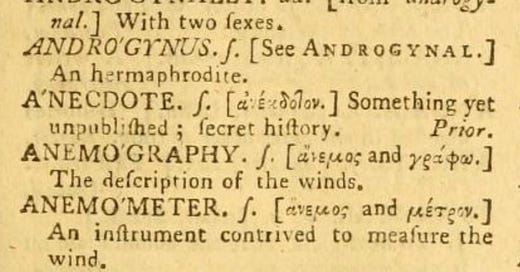

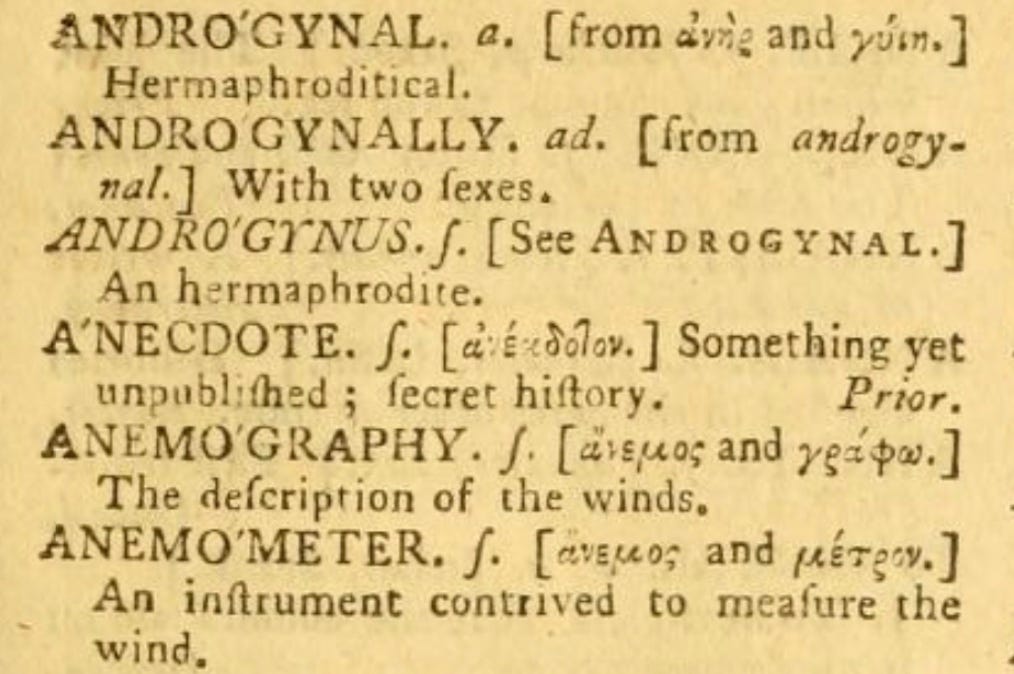

I looked it up and indeed, there is Anecdote in Johnson’s dictionary, right between Androgynus and Anemography. Wind speed and gender fluidity have been concerns for hundreds of years.

“All the world read anecdotes; but not many with reflection, and still fewer with taste. To most, one anecdote resembles another; a little unconnected story that is heard, that pleases and is forgotten. Yet when anecdotes are not merely transcribed, but animated by judicious reflections, they recall others of a kindred nature: and the whole series is made to illustrate some topic that gratifies curiosity, or impresses on the mind some interesting conclusion in the affairs of human life.”

And for readers of long histories:

“A well-chosen anecdote frequently reveals a character, more happily than an elaborate delineation as a glance of lightning will sometimes discover what had escaped us in full light.” “We are more acquainted with the character of Sir Thomas More, by his jocularity on the scaffold, than by some lives which are to be read of him.”

(This by the way, is true.)

Isaac’s father Benjamin Israeli changed his name to D’Israeli in 1748, after arriving in England from Italy. He married the Jewish daughter of a local merchant and Isaac as a young man inherited great wealth from him and could spend his time on literary studies. He was a regular at the British Museum and was described by Washington Irving in 1817 as “a dapper little gentleman in bright coloured clothes, with a chirping, gossipy, expression of countenance, who had all the appearance of an author on good terms with his bookseller.”1

Wait, what? Yes, here is Washington Irving running into Isaac D’Israeli at the British Museum at a turning point in his (Irving’s) life, just before he went bankrupt and realized he would need to turn to writing for his livelihood. Two years later Irving published: The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent (1819-1820), which includes the famous Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.

It with this history in mind that I feel good about our Monday morning New Yorker “what’s the anecdotal value?” question as we debriefed from weekend dates. We were in the marketing and promotions department of The New Yorker, some floors below editorial. We weren’t professional writers and had no formal outlet for our storytelling. My favorite from the era was about a dinner fixup at a fancy place, I think Le Cirque. The date requested a doggie bag for his leftovers. The couple went to a club afterward and, as the story went, the young man kept glancing at the table to check on his doggie bag. There was, we agreed, no chance of a second date.

This anecdote circulated among us for months, if not years. “Did he ask for a doggie bag?” was always the first question after all dinner date stories. We all asked our mothers whether we were wrong: whether the demonstrated thrift was a good sign, not a bad.

There were anecdotes about what the date wore, about one who was only attractive when he faked an accent, one who walked with his feet like clock hands at ten and two o’clock.

An old Harvard friend from the PhD program in economics when I was at the Kennedy School, confirmed I would go on and on about anecdotal value in the late 1980s, pondering political anecdotes. He offered solid critiques of my current model, including urging me to think harder and differently about value. What is the positive value of negative anecdote?

So yes, the genesis of my interest was personal, but the interest in approaching value methodically has evolved into a professional concern.

“Literary biography cannot be accomplished without a copious Use of Anecdote” D’Israeli writes. “Anecdotes of an Author serve as Comments on his Works.” “A Writer of Talents sees Connexions in Anecdotes not perceived by others.”

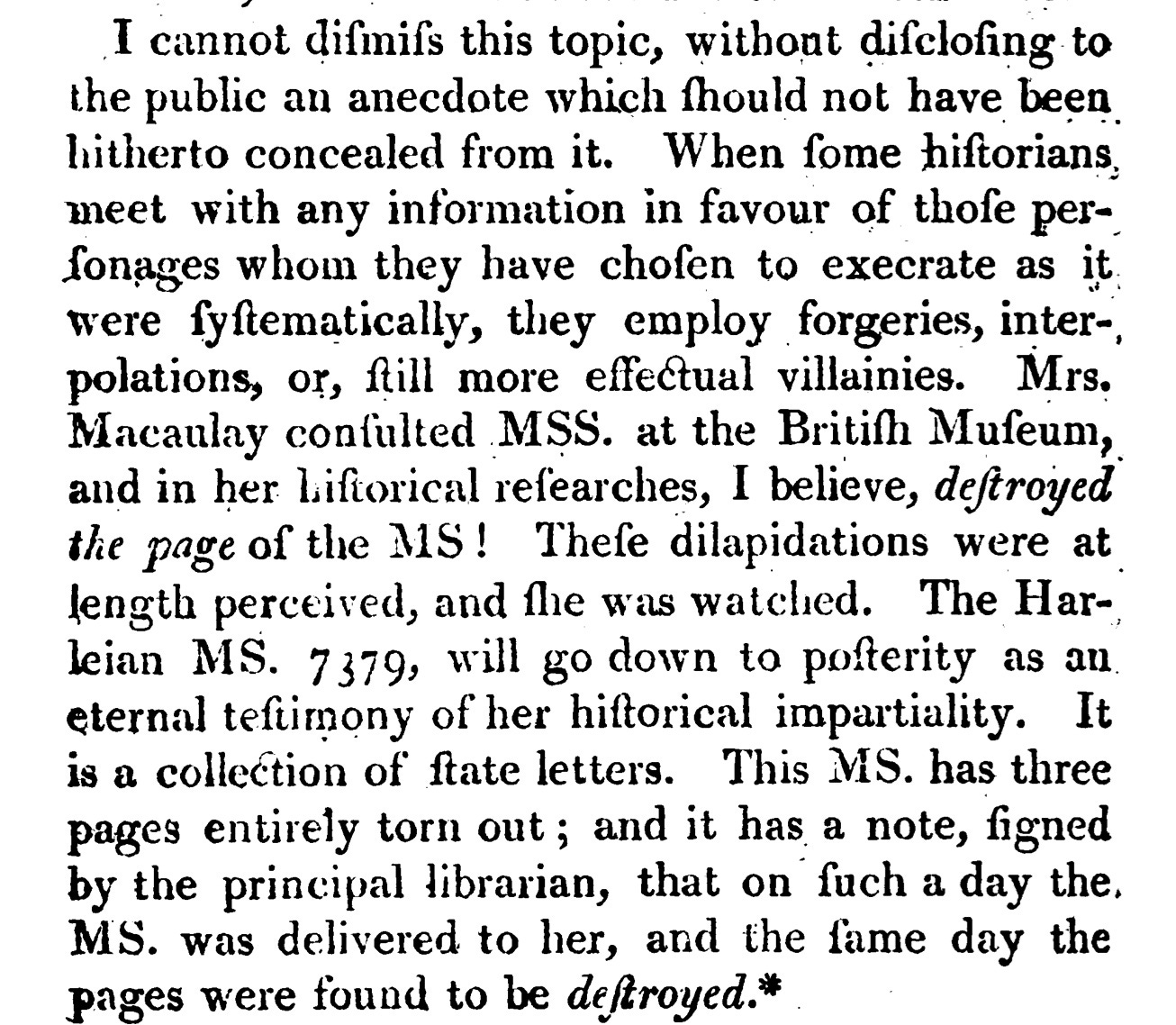

Isaac D’Israeli ends his dissertation on anecdotes with a startling and somewhat libelous anecdote about the Whig historian Catharine Macaulay destroying government documents that would have contradicted her eight-volume A History of England from the Accession of James I. to that of the Brunswick Line (1763-1783), which supported the regicide of Charles I.

“I cannot dismiss this topic, without disclosing to the public an anecdote which should not have been hitherto concealed from it,” he begins, then describes how, at the British Museum, she destroyed several pages of a collection of state letters by ripping them out. He notes that where the papers should be there is “a note, signed by the principal librarian, that on such a day the MS. was delivered to her and the same day the pages were found to be destroyed.”

The anecdote is political genius – is there a better way to disparage a rival historian whose revolutionary views are diametrically opposed to your own conservatism by accusing her of destroying historical evidence? Someone might check (Harleian MS 7379): maybe Isaac made this up!

To return to Washington Irving, who clearly watched D’Israeli closely:

“I was curious to see how he manufactured his wares; he made more stir and show of business than any of the others, dipping into various books, fluttering over the leaves of manuscripts, taking a morsel out of one, a morsel out of another.”2

Irving understood that the best stories aren't just entertaining—they're mirrors reflecting the peculiarities of human nature and a new nation. Whether it's a schoolmaster fleeing through the dark woods of Sleepy Hollow or an overly frugal suitor guarding his leftovers at a 1980s nightclub, the tales we tell expose our foibles, our fears, and occasionally our genius. Isaac D’Israeli found his stories in the British Museum, Irving found his both there and in the misty hollows of the Hudson Valley; we found ours in slow elevators and chance encounters at The New Yorker. But the principle remains the same: a well-chosen anecdote can illuminate character more brightly than a thousand-page biography.

Shane, A. L. "Isaac D'Israeli and his quarrel with the Synagogue—a reassessment." Jewish Historical Studies(1982): 165-175.

Rubin-Dorsky, Jeffrey. "Washington Irving and the Genesis of the Fictional Sketch." Early American Literature 21, no. 3 (1986): 226-247.

Pope Francis approves of (humorous) anecdotes: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/17/opinion/pope-francis-humor.html

"Popes, too. John XXIII, who was well known for his humor, during one discourse said, more or less: “It often happens at night that I start thinking about a number of serious problems. I then make a brave and determined decision to go in the morning to speak with the pope. Then I wake up all in a sweat … and remember that the pope is me.”

"How well I understand him. And John Paul II was much the same. In the preliminary sessions of a conclave, when he was still Cardinal Wojtyła, an older and rather severe cardinal went to rebuke him because he went skiing, climbed mountains, and went cycling and swimming. The story goes something like this: “I don’t think these are activities fitting to your role,” the cardinal suggested. To which the future pope replied: “But do you know that in Poland these are activities practiced by at least 50 percent of cardinals?” In Poland at the time, there were only two cardinals."

If you ask Google Gemini (premium) to do a deep dive about Benjamin D'Israeli and Washington Irving it says this: "While a direct relationship between Benjamin D'Israeli and Washington Irving remains unconfirmed, their overlapping contexts and shared interests suggest the possibility of indirect connections. Both were influential figures in their respective domains, leaving a lasting impact on politics and literature. D'Israeli, a British Prime Minister of Jewish descent, navigated the complexities of British imperialism and left his mark on the Conservative Party. Irving, a celebrated American author, pioneered American literary traditions and gained international recognition for his captivating stories and insightful observations of society. Their shared interest in history, social commentary, and human nature, along with their connections within literary and intellectual circles, hint at potential points of convergence in their intellectual journeys. Further research into their social networks and literary influences might reveal more insights into their potential interactions and shared intellectual landscape."